As an undergraduate at Stanford I’ve worked with the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR) and Stanford in Government (SIG) to organize two separate policy hackathons on the topics of Affordable Housing and Criminal Justice Reform.

At each of these events, dozens of students competed in teams to create policy proposals and accompanying analytical tools to be evaluated and scored by expert panels of judges from academia, government, and the private sector. Following each hackathon, a few teams have continued working with judges on their policies/tools to pitch them to organizations and government bodies working in each space.

The goal is to provide students with the space, support, and motivation to think critically about problems of public significance and hopefully generate ideas or tools that can be useful to those working toward policy reform or innovation. Partners who either organize or judge the hackathon can use it as a space to recruit talent or generate ideas that they can develop into technical tools or implementable policy.

In this brief I will outline the steps required for organizing a policy hackathon. This brief will be broken up into sections on purpose, topic, judges, hackathon logistics, and marketing. Hopefully it will be of use to others in universities or governments who want to experiment with making new policies in more collaborative and inventive ways. It links into the growing literature on policy design and innovation, as well as agile governance and prototyping policy — contributing concrete details on how to actually run a successful event, in particular with university students.

What’s the purpose of a Policy Hackathon?

Undergraduate policy hackathons/sprints serve as a vehicle for engaging students with real-world policy problems, generating new ideas and tools that can be useful to policy professionals, and connecting students with the skills, mentors, and experience for pursuing a career in public policy. The event can expose students who may otherwise have never considered a career in public policy to the experience of working on a real-world policy problem while also providing students who plan to work in or around public policy a chance to distinguish themselves outside of the classroom and work on a project with the potential to be implemented in the real world.

If published widely, the event can be educational for the general public who can observe the event or serve to increase conversation about a policy issue. Partner organizations can use this space to generate new policy proposals or tools, recruit talent, or train the next generation of policy professionals.

How do you choose a topic?

The organizers of a policy hackathon should shepherd the work by scoping a topic that is concrete and engaging. A good topic is specific enough that a group of laypeople can learn enough to make informed commentary about it in a short period of time (a week to a month), but broad enough to allow for creativity and a diverse group of work products. Topics such as increasing wage growth or education reform are too broad, while topics such as properly calculating the poverty line or designing the most effective EITC are too narrow. Properly scoped topics could include proposals/tools to promote successful re-entry post-incarceration, lower infant mortality rate in the United States, or ensure California reaches its carbon emissions target.

Topics should not privilege students with a given political ideology or methodological approach, but instead be based on clear criteria about how effectively their policy would meet their target goal given real-world constraints. Topics should be selected with both potential judges and your group of participants in mind.

Topics should be selected such that your institution is able to solicit judges with relevant subject-matter expertise that can lift-up promising projects after the event. Topics should also be selected that will excite your participants by allowing them to work on an issue that tangibly impacts people’s ability to live meaningful lives, especially if participants are typically unable to affect the issue in their normal lives.

Who should be the judges, and what should they do?

Another key part of the hackathon is securing judges to provide the concluding review at the end of the event. The judges’ purpose is to score each project, provide feedback on each project, and to connect teams with outside actors if they believe a project could be used in practice. An ideal judge would have relevant expertise to evaluate the quality of the proposals, connections to promulgate team’s projects, and a willingness to mentor and help teams grow through critique.

It’s important that the judging panel has judges with a variety of skill-sets and backgrounds so that they can provide feedback from different perspectives and connect students to professionals that are most relevant to their projects. The time commitment for judges is a single afternoon (3–5 hours) on the final day of the hackathon.

The details of Logistics + Outreach

Ideally, the hackathon itself should take place during the first few weeks of a term so that students have the lowest workload and the greatest number will be able to participate. Survey data has shown that this timeframe is preferred by students by a wide margin.

The general topic of the hackathon should be announced and sign-ups should open 6–10 weeks before the start of the hackathon. Students should be encouraged to form interdisciplinary teams as various components of the hackathon favor students with differing technical, analytical, and communicative abilities. Students should be given the option to enroll as individuals so that they can join already existing teams or form a team with other solo sign ups. Teams with at least one first-year could be eligible to compete for a designated honorable mention. Both of these design choices work to make the hackathon more accessible. The judge line-up and a slightly more specific topic should be announced 4 weeks before the start of the hackathon.

The hackathon itself should take place over 8–10 days, a full week with two weekends. At the start of the hackathon, a launch event should occur where the full topic, suggested datasets, and judging criteria are announced. Students should be allowed to conduct interviews with relevant stakeholders, use publicly available data, or submit FOIA requests to acquire data. This event should also serve as a forum for teams to ask questions. If possible the launch event should be recorded and made available for all teams to review at will. To encourage access to and quality of work products, organizers can host additional skills trainings or circulate guides for policy design, data analysis, or oral/written communication. Throughout the week, several “office hours” sessions should be held where mentors (pre-doctoral or graduate students in social science fields) are available to provide feedback, guidance, and technical assistance for interested teams.

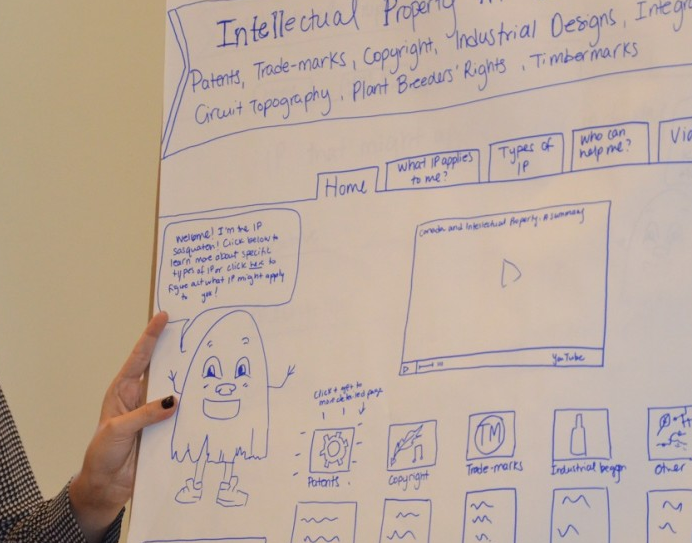

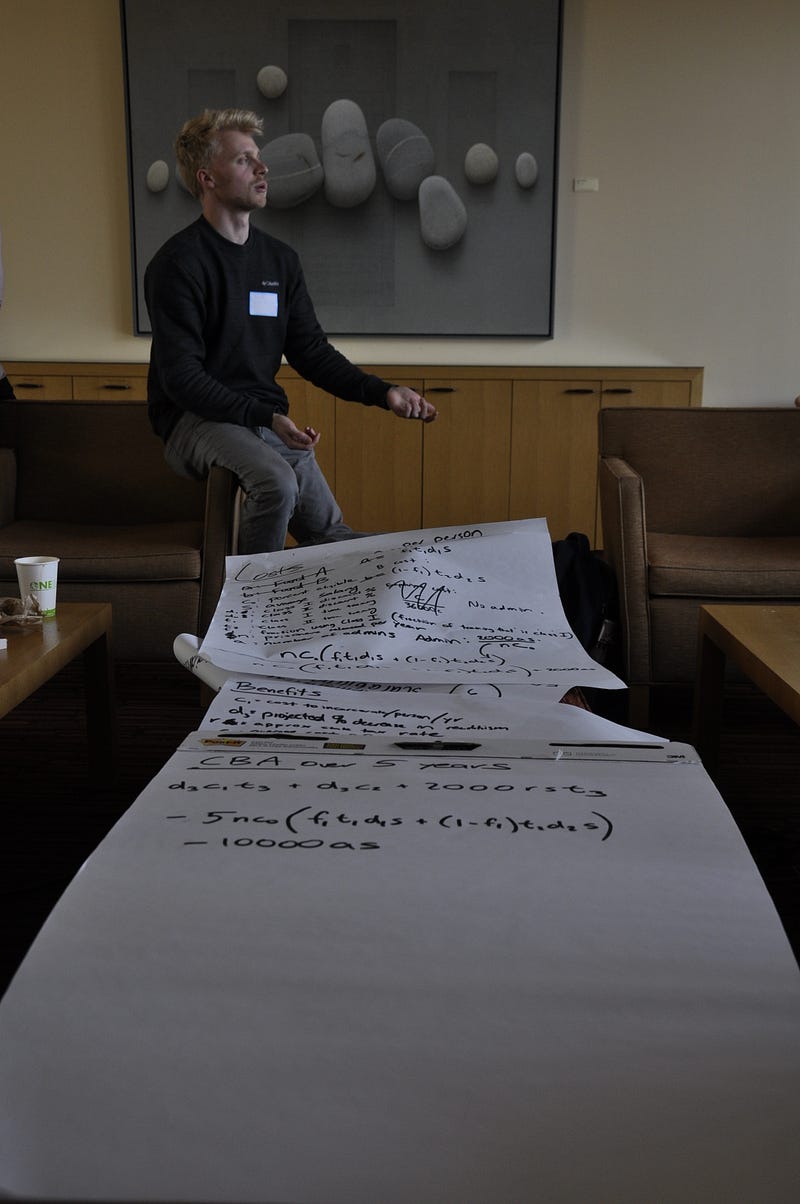

The final day of the hackathon should consist of a full work day followed by a pitches event. The work-day should occur in a single designated space from early in the morning until the afternoon at which mentors are available to assist teams. By the end of the work-day teams are expected to submit a policy memo, some sort of tool, and a slide-deck. The technical tool can be anything ranging from an Excel spreadsheet that provides a cost-benefit analysis for the policy, a compiled data-set with summary statistics, a machine learning algorithm, or a prototype for an app designed for policymakers or the public to use.

If more than 8–10 teams are participating, mentors/judges should evaluate the policy memos to narrow down to 8–10 teams. The selected teams should then present brief pitches and take questions from the judging panel.

This pitch event can be opened and advertised to campus or the general public to observe. It can also be streamed online to amplify the event’s audience. Following the pitches, teams should be provided dinner or be allowed to leave to acquire dinner while the judges deliberate.

During deliberations, judges should score each project based on agreed upon criteria, provide written comments for each team, determine a winning team, and decide whether to provide any honorable mentions. Winning team(s) can be compensated with some sort of prize, cash or otherwise. This prize can serve as a large incentive for students to participate.

Following deliberations, judges should announce winners and if they desire, make themselves available to talk to teams to provide more feedback or connect with them if they wish to keep mentoring them or have them pitch their project to an outside group. It is important that student and judge input be solicited during and after the event so that the event can be improved if it is to be repeated.

Taking Policy Hackathons Forward

Following the hackathon, the hosting institution should provide all students with support to continue working on their project if they desire to. This support could come in the form of occasional advising from faculty, a stipend for research, or a position in a lab at which some portion of their duties would be to continue working on their project.

Historically, successful policy recommendations have communicated a clear causal story about the source of the problem, made a compelling case for why their policy change would alter the incentives or capacity of actors or institutions that operate within the ecosystem of the problem, and been designed to be fiscally and politically implementable under real-world conditions. Successful tools have been conceptualized to solve a previously identified problem of a clearly identified stakeholder group, been designed intentionally for the needs of that group(s), and often adopt similar strategies that have been used effectively to solve problems in different disciplines.

I encourage students, professors, and administrators at other universities to organize their own policy hackathons as a means to provide students with a unique space in which they can apply their skills to generating solutions to real-life policy problems, use ideas and prototypes generated from this exercise to design implementable policies or tools, and expose students who may not be thinking about a career in public policy to the field. Often student’s perceptions about possible career paths are shaped by what they see around them and so long as there aren’t hands on ways for students to engage with policy many will view this work as unattainable.

Can You Run a Policy Hackathon?

The structure described above could also be used by university courses, NGOs, or government bodies as a means to generate ideas in a low-stakes environment designed to maximize creativity. Each organizational group would need to make alterations to fit their participant group and outcome goals, but the general structure should be transferable. If you’re interested in running your own, please be in touch!

In addition to hackathons, educators + organizers should also consider some other strategies to promote these kinds of opportunities. This could include policy-memo writing contests. Or it could be more substantial: starting labs that work to train and support undergraduates interested in policy design and innovation. These labs can also be used as vehicles to further develop policy ideas or advise governments or NGOs.

Hackathons are becoming an increasingly popular programmatic approach for undergraduate competitions at Stanford. Stanford currently holds several other campus wide hackathons open to undergraduate students on a variety of topics including TreeHacks, Health++, Arts Hackathon, and Big Earth Hacks. To our knowledge, the SIEPR/SIG Policy Hackathon is the only hackathon at Stanford that has a policy focus.

A handful of other colleges and university have developed policy-oriented hackathons or policy competitions and challenges including MIT, NYU, University of Pennsylvania, Rice University, and American University, but the concept of a “Policy Hackathon” remains relatively rare — though hopefully will be spreading further.

—

Originally posted on Legal Design and Innovation, By Michael Swerdlow