At a recent legal design workshop at University of Bologna in Italy, our Legal Design Lab team collaborated with a team from the university there, as well as service and data designers, including from Facebook. Our goal was to explore how to communicate difficult legal terms and technological concepts about data privacy, in ways that more consumers could understand.

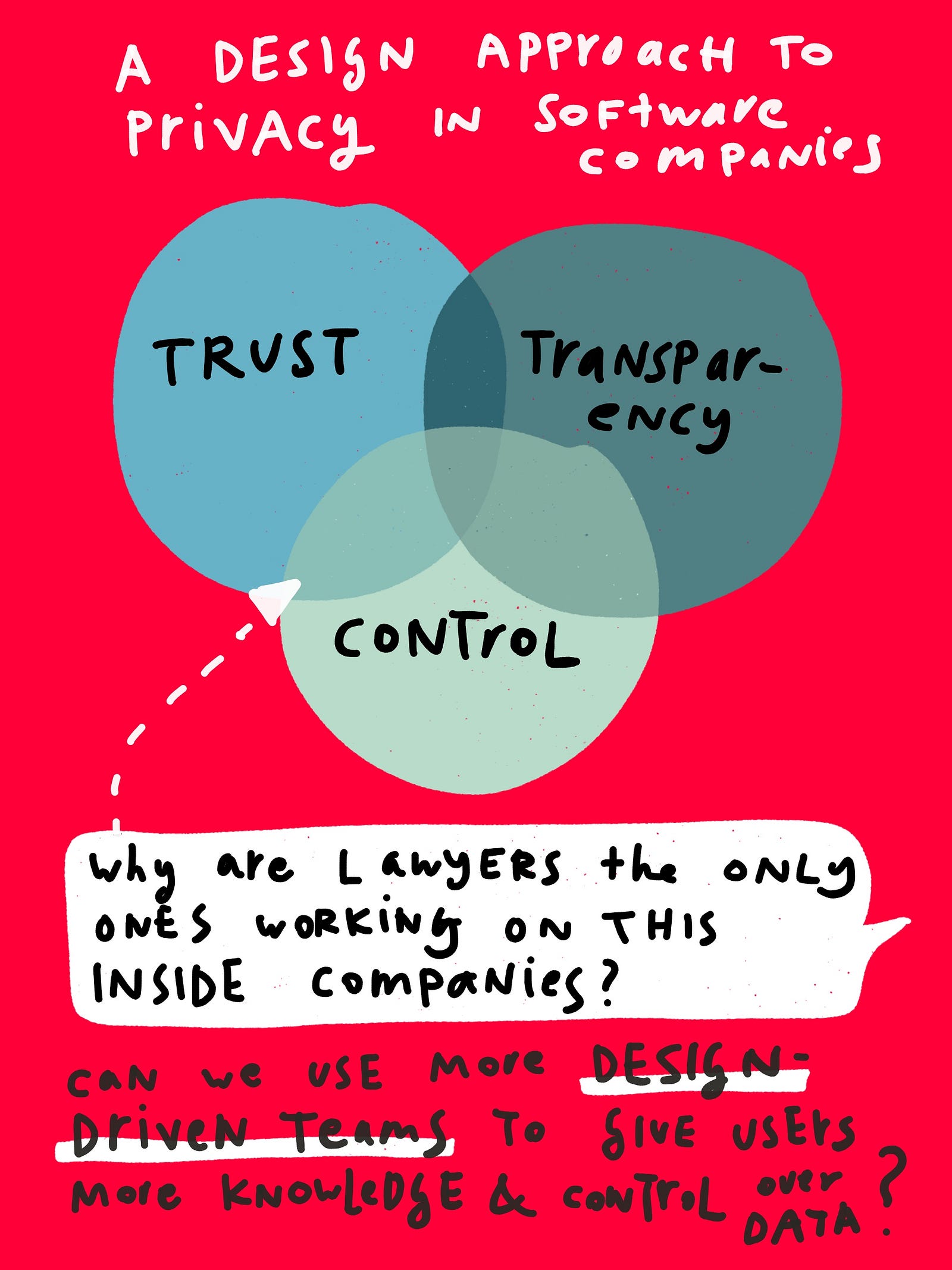

With the European GDPR ushering in a new mandate for companies that control and process data to better inform people about their practices, and ensure higher quality consent is given — this need for legal design is much larger. Legal design can bring a more methodological and user-centered approach to making these disclosures and consumer contracts.

Our team will be writing a more proper write-up of some tests that we ran while there. For now, we wanted to summarize some of the insights that emerged during our day-long workshop and follow-on debrief and testings.

1. Facelift the policy document or abandon it?

One of the big debates under the surface was whether visuals within the traditional data privacy policy were worthwhile or not. This has been one of the most popular proposed methods to improve engagement and comprehension of legal documents: to include more icons that represent the text, in order to help users flag and navigate content, and to make the abstract words come alive.

But there was not universal agreement that visuals were a worthwhile investment for effective privacy communication. Others, especially coming from a service and interaction design point of view, argued that we should rethink the policy document altogether, rather than try to spark engagement with it. It wasn’t icons in particular that were not worthwhile, from this perspective. It was any visual or interaction design treatment of the traditional privacy policy document.

From this point of view, it’s time to abandon the traditional privacy policy as a consumer-facing tool (though it may be fine to keep it for the regulators). If we just acknowledge that the lengthy legal document may be a lost cause for most consumers — it is simply too long, too decontextualized, and too legalistic for them ever to engage with. Instead, we should invest our thought and resources into where else communications about data privacy may be relevant. Can we make those communications shorter, more contextual, and more interactive?

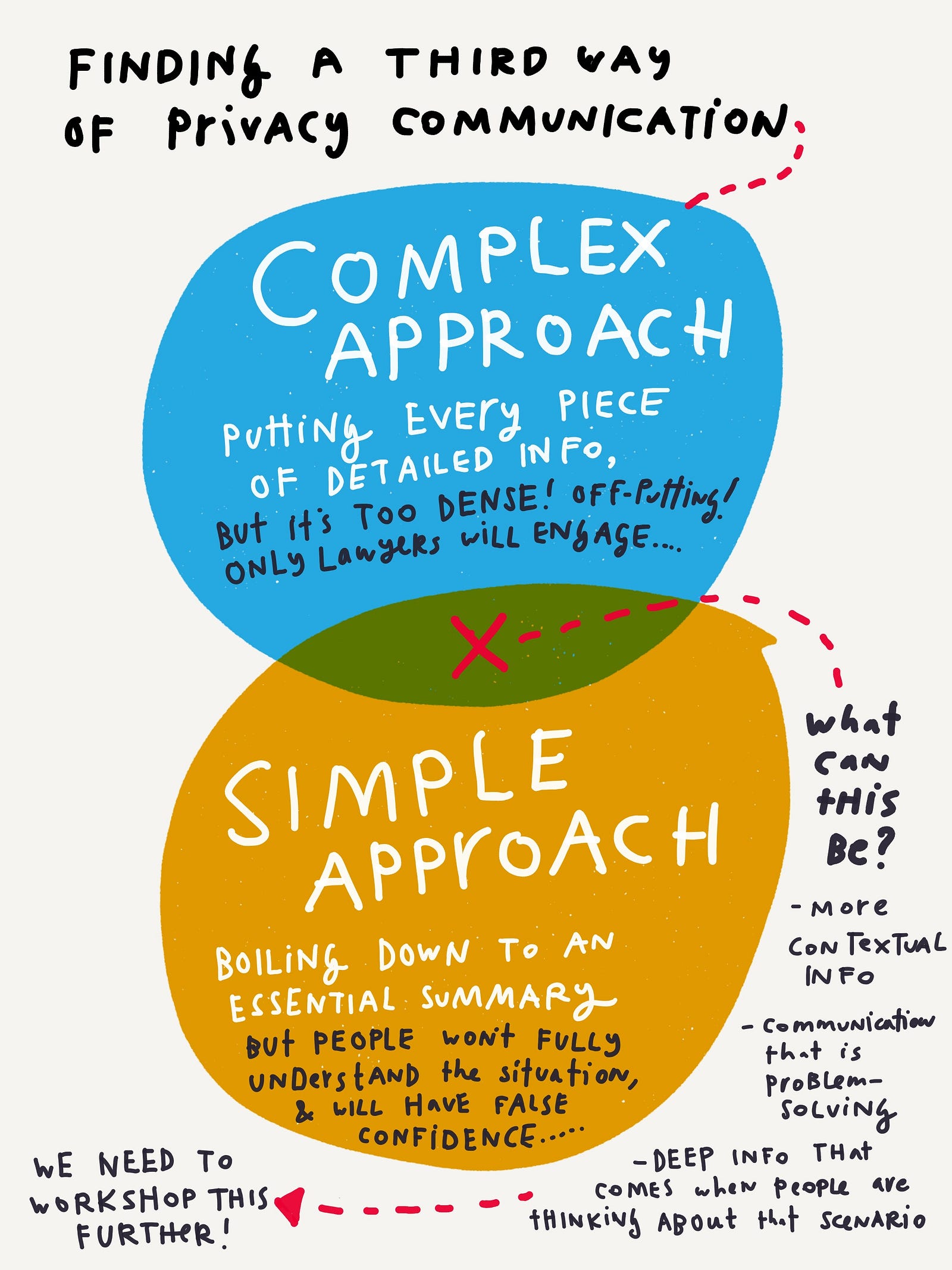

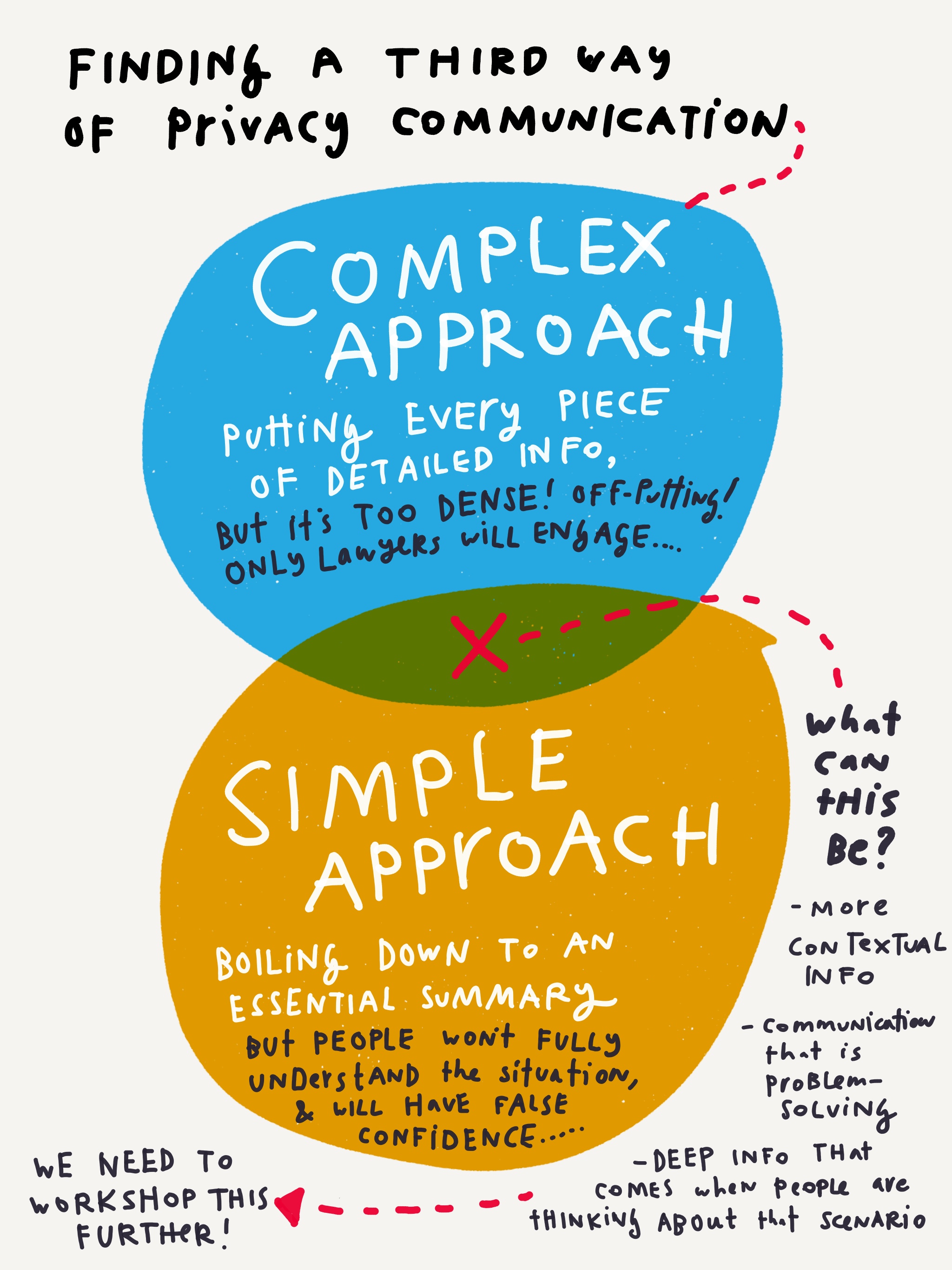

The big challenge for lawyers and designers is to find the right amount of information to communicate. Not too simple, so that it gives false confidence about what the practices are — but not too complex that makes consumers tune out and look away.

2. Can we crowdsource or sync data privacy education?

Another theme was around making more systemic data privacy communication strategies. For example, is there way for the crowd of consumers to tag policies to surface the key points or to question or to explain them? Or, is there way for different software companies to sync their policies in ways that they are not constantly trying to educate consumers about the same terms and conditions, but that they share and spread this education across them?

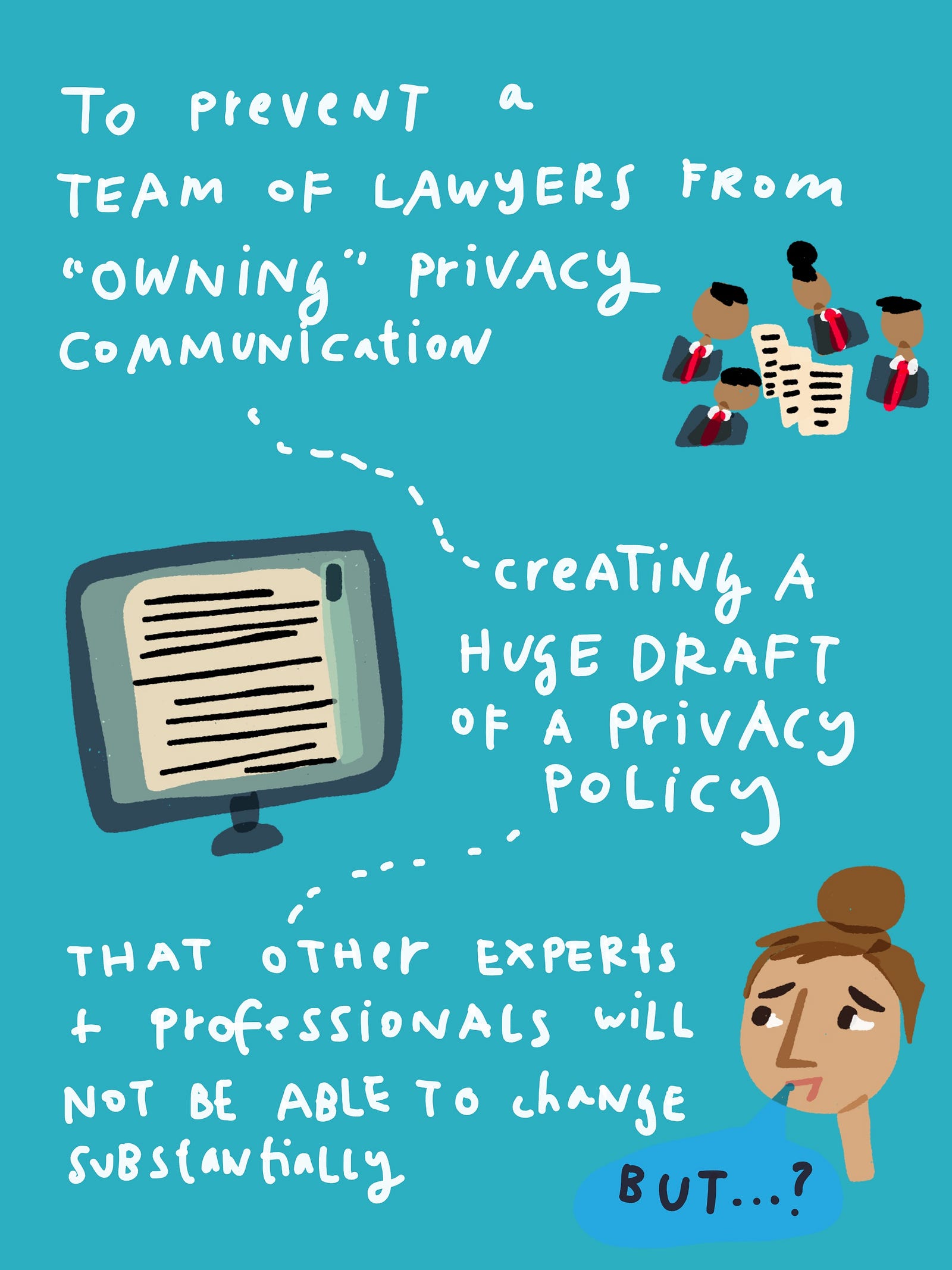

3. Taking Ownership of Privacy Communication away from Only Lawyers?

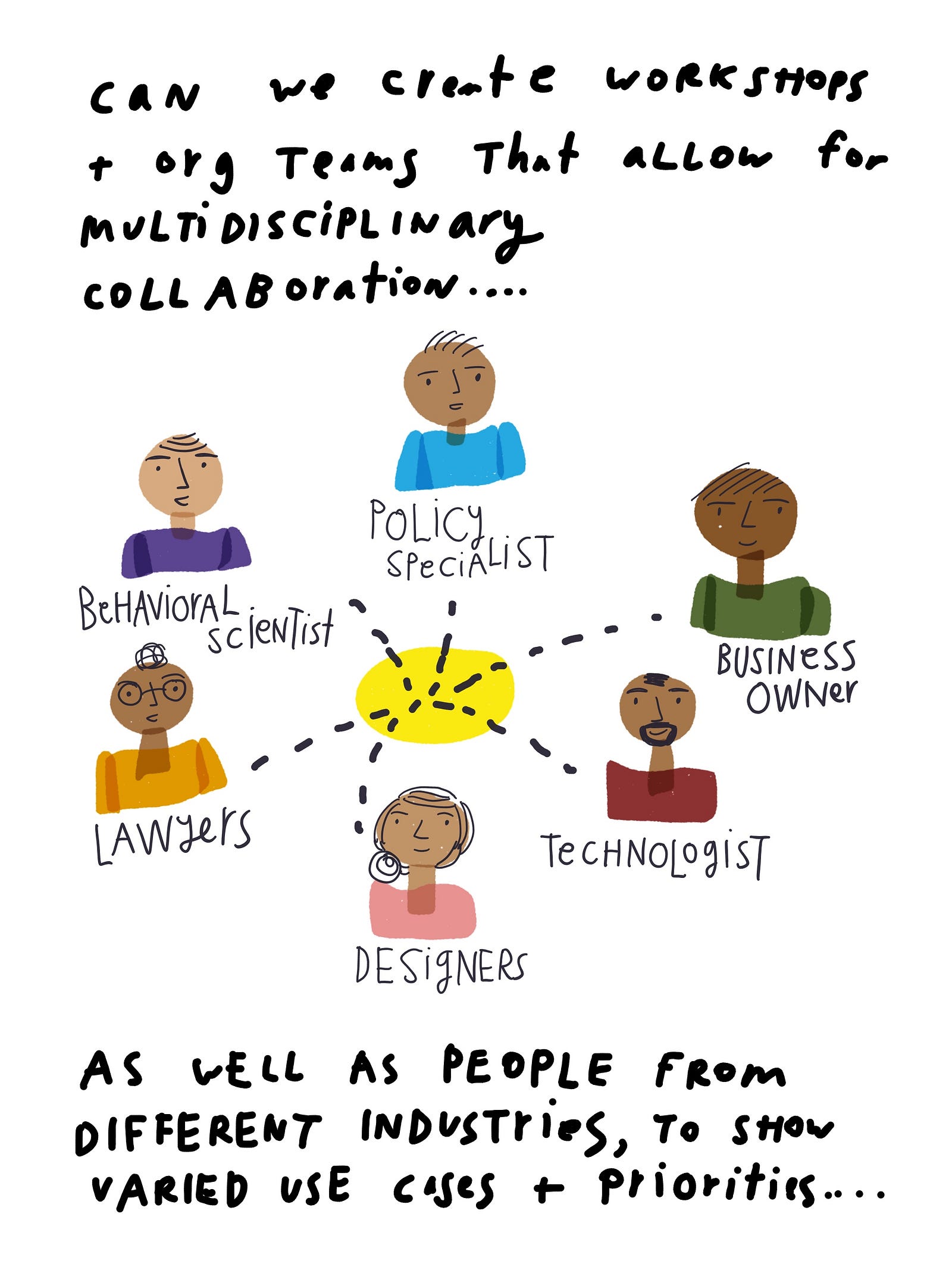

A final overarching theme of the workshop was the need for more diverse and interdisciplinary groups to work on these challenges. Of course lawyers and privacy professionals must be included, but perhaps they should not be managing the process of crafting the privacy communications. We need more professionals involved, who can think about engagement, services, and interactive technology to create better education around data privacy — and more control for users over it.

That said, to get lawyers to work with designers and technologists on this — we need to offer incremental mechanisms. Coming back to icons, the are attractive to lawyers because they are not too disruptive of the current model of privacy communication. They complement the legal text, rather than replacing or transforming it. Perhaps icons can be a strategy to attract lawyers to legal design, but still we need more designers and technologists with power inside privacy groups in order to fundamentally rethink how consumers get notices and options around their data.

We thank our workshop participants from the University of Bologna’s CIFRID, especially Monica Palmirani and Arianna Rossi; Facebook’s Trust, Transparency, and Control Lab — including Dan Hayden and Victoria Duchatelle; Normally design studio’s Chris Downs; and Stanford Legal Design Lab researchers Emma Eastwood-Paticchio and Tom Davidson. Many (if not all) of the insights above are from them!

1 Comment

[…] Source: Rethinking Data Privacy Communication Design: 3 big questions from Bologna […]