By Ayushi Vig, This was originally posted in our Medium publication Legal Design and Innovation

In Community-Led System Design, a Stanford Law School/d.school course this quarter, we are speaking with people working on systems- and policy-design projects, from a human-centered design perspective. One of our guests was Verena Kontschieder, a visiting research student at the Center for Design Research.

Verena’s topic was the growing number of Policy Labs in governments and intergovernmental organizations — and how more policy-makers are using design approaches for better governance and systems change.

Design approaches to crop theft

Verena began her talk with a case study how design is coming into policy-making: regarding praedial larceny in the Caribbean subregion.

Praedial larceny is the theft of growing crops. It had been the most significant crime in the region for over two decades, with its rate of occurrence only rising.

At the international governance level, policymakers and the Food and Agriculture Organization had been conducting constant research on praedial larceny in efforts to reduce the problem. They found that only 45% of all cases were reported and traced. They interpreted this as being due to the inertia of the region’s police forces, which led to wide frustration and distrust among people. Still, however, they were not able to improve the situation, and the occurrence of PL continued to rise.

Three years ago, the FAO decided to try a new approach. Together with the World Bank, it worked with multiple NGOs, civil society organizations, and trade unions to conduct on-the-ground design work. These organizations interviewed hundreds of people who had been affected by and involved in praedial larceny in some capacity. Very quickly, they discovered that the problem was not the police; rather, it was a combination of shame and societal structure. People were not reporting cases of praedial larceny out of a fear of being marginalized, as the stigma of being an informant in that society was just too high.

This case study was significant for me because it vividly illustrated how research at the international governance level can fail to capture the reality of the people on the ground (such as for over 20 years in this example!). As Verena pointed out however, it is important to remember that both these approaches are valid, albeit in different contexts.

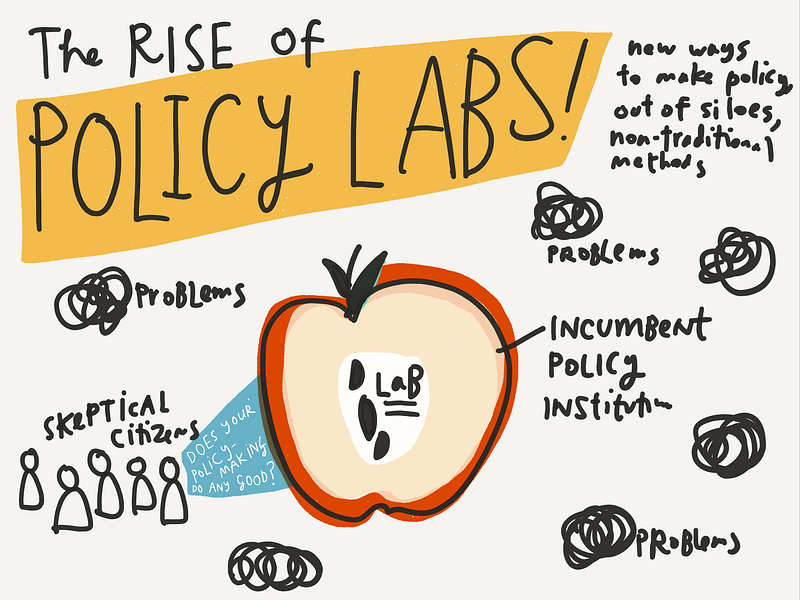

The rising Labscape

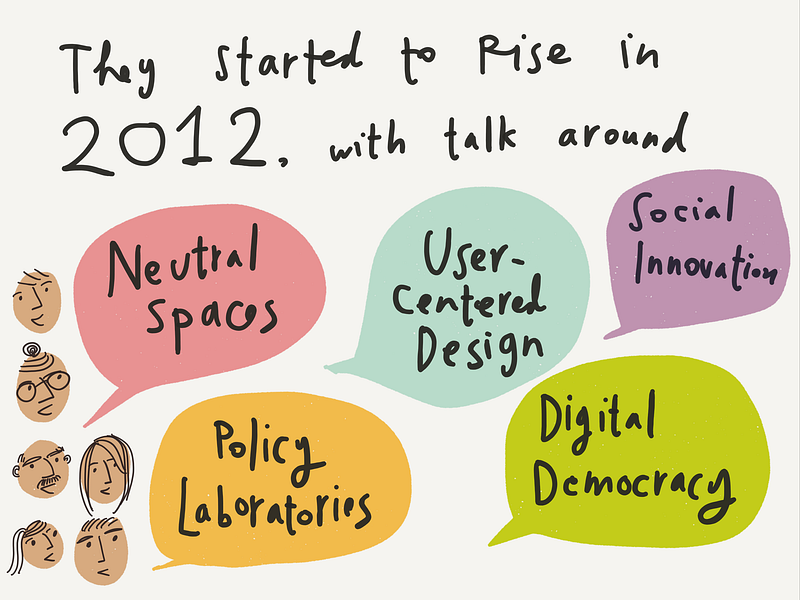

This case study also illustrates a shift in paradigm that is currently occurring worldwide. Verena called this a shift towards “labscapes”, i.e. policy labs working across landscapes while also acting as a “safe place to do dangerous things”. This lab movement is driven by academia, business, government, and the private sector, and has been particularly prominent since 2012.

These policy labs, such as the African Development Bank Policy Innovation Lab and the Laboratorio de Gobierno, are taking on different shapes and formats, but the nature of their existence is similar. They are all working to enable stakeholders to come together in a physical space in the face of complex policy changes in manners not addressable in traditional institutions, while at odds with traditional policymaking.

Verena also discussed her own Ph.D research, which consists of multi-sited case studies on policy labs at the international governance level, with the goal of examining the intersections of innovation, policy, and design.

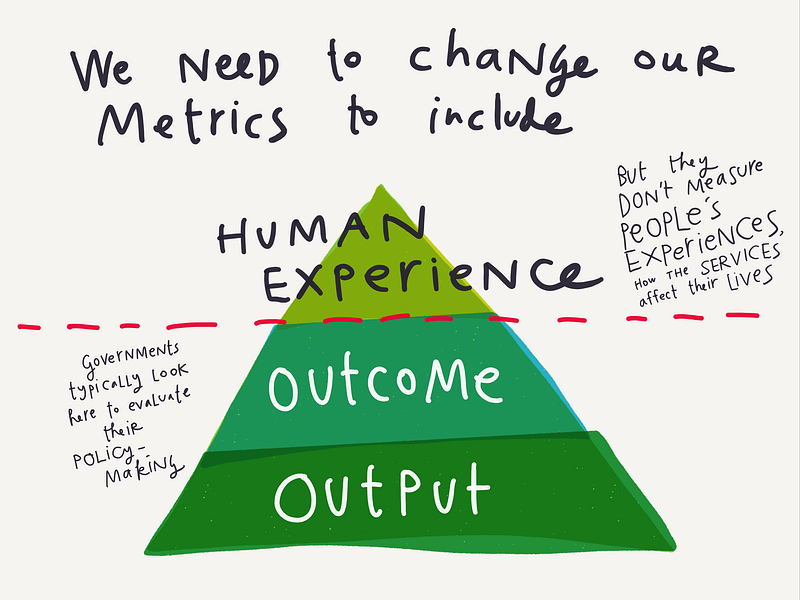

One of her key findings thus far is that there is an institutional vs. individual level break in the labspace. Policy and society are detached at various levels; policymakers and institutions lack transparency and often even direct accountability, and there is, as a result, a sore lack of institutional trust on behalf of citizens, who feel extremely alienated from these higher-up levels of governance.

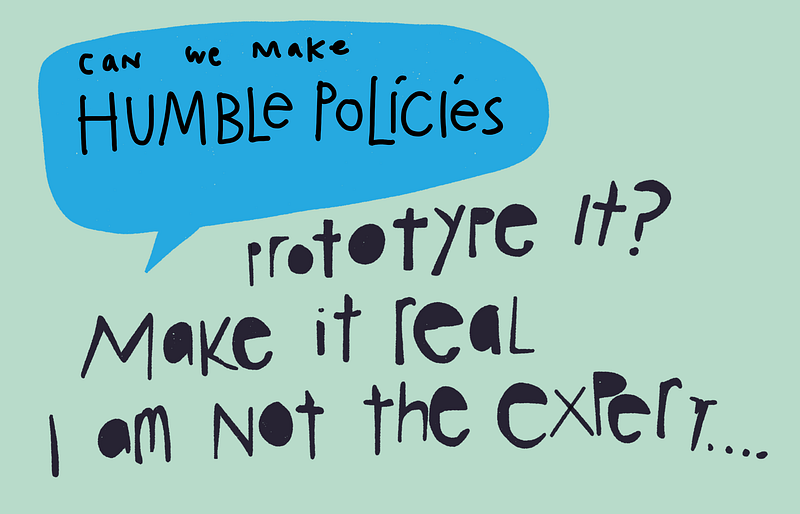

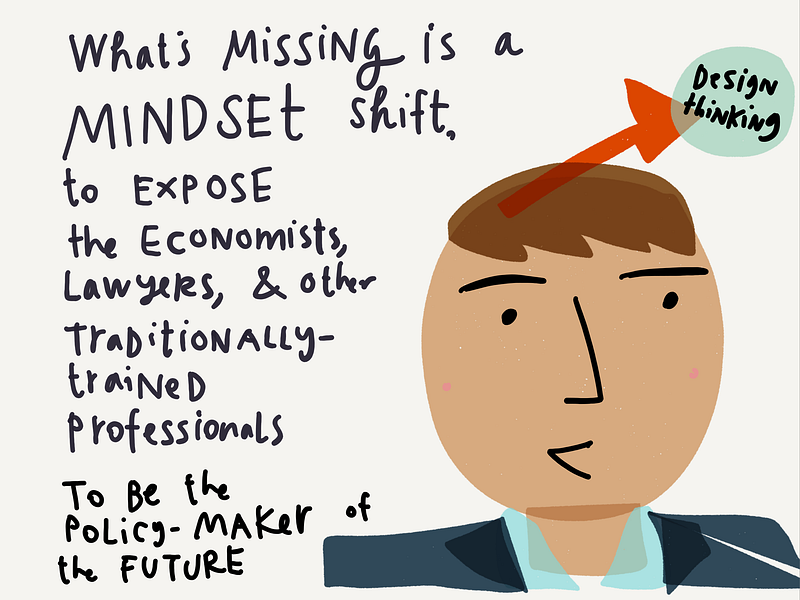

Verena emphasized that humility should be a key aspect of any design process — as designers and policymakers, it is important to know that we are fallible and no longer the experts. Rather, we need to be sourcing the experience and knowledge of communities directly affected by the issues we seek to tackle. Verena also raised the question of what the role of policy and policymakers should be, and whether it should just be one of enabling NGO’s and/or the private sector to tackle social problems.

Verena ended by raising several thoughtful and important questions that are emerging from her research:

1. Are policy and political incentives misaligned? Is innovation possible in the absence of market incentives?

2. Are out-of-lab policy initiatives not innovative? If not, why is innovation not happening outside the lab?

3. As designers, should we strive to reformat entire organizational systems, or let design trickle down organizational hierarchies to produce meaningful change?