This quarter, I’m co-teaching a class, Community-Led System Design with Janet Martinez at Stanford Law School/d.school. We are bringing various innovators who are doing human-centered design work in government and legal systems. We, and our students, will be documenting what we learn during this class from our guest speakers and our own work.

Our first visitors were Chelsea Mauldin and Shanti Mathew, from Public Policy Lab in New York. We have admired their work on affordable housing, social support services, and public health work — all done with tremendous respect for the communities they’re serving and methods that put community-members’ voice at the center of decision-making.

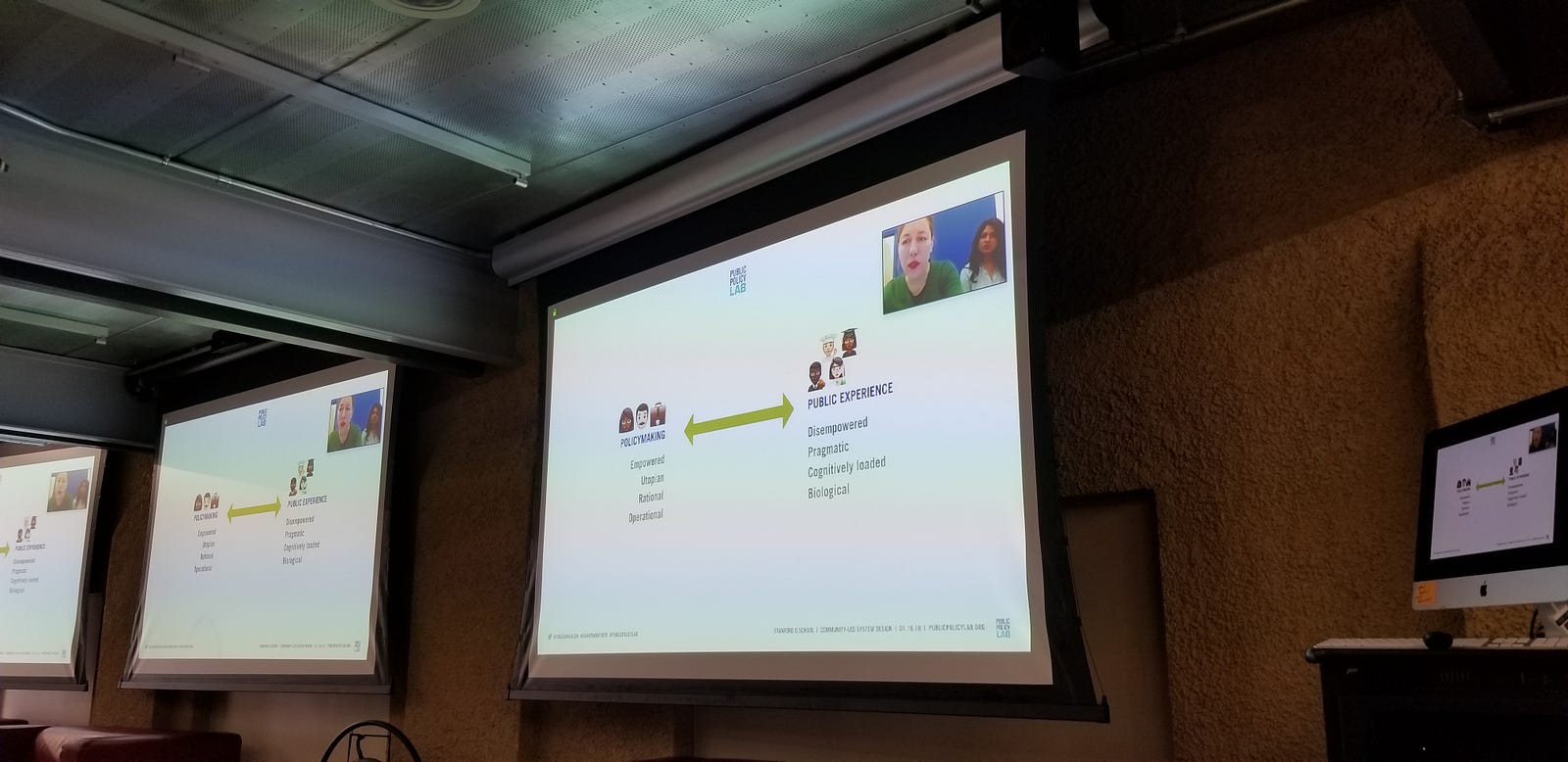

Chelsea and Shanti joined us virtually from their New York office, to discuss their approach, their projects, and insights for future public policy innovators.

As you can explore on the website, the Public Policy Lab team works with municipal and federal agencies. As a non-profit, the Public Policy Lab is an independent group, but they work closely with partners inside the government to create new initiatives to better deliver services and support to the public.

They work at a core point of friction: between the policy-maker’s point of view, which often is utopian, rational, and bureaucratic — and members of the public’s point of view, which often is pragmatic, cognitively overloaded, and disempowered.

They have figured out ways to use design to better identify opportunities and test them. This means going through a few phases — of doing research and identifying key problems and opportunities, then co-creating, prototyping, and testing with community members, and finally refining and doing storytelling and market-building.

If you do one project with a policy-maker, you might set a new example inside the organization. A human-centered process can change the posture of the agency toward the public they serve — there are ripple effects on how people in the agency interact with the public, and how they set up services.

How can you find the right partner?

Some possible project partners are motivated by the group’s own concern for some big societal issues — and other times it is the government agencies who come with issues (sometimes with funds or not). Some of the work is funded by philanthropic grants.

The Lab team has found wonderful partners in the government, who are smart, dedicated policy-makers — who are passionate and engaged. What is challenging is that public agencies are complex entities, so there is a huge number of moving pieces with distributed authority. Some of the challenges that have arisen:

- How can you make change in a complex system that isn’t particularly top-down (one person can say change this, and everything changes)?

- To what degree do our partners have power and influence? We need to come up with a plan that speaks to their power and constraints.

When the Lab is scoping partners, they need to define ‘What does success look like?” and “Who is involved in this system”? There will never be enough time or money to do all the things the group wants to do. So they ask:

- What do we want to get to? Let’s define success concretely.

- Who are the people involved in service-delivery? Whose agreement do you need to get to make changes on the ground? If they want successful implementation, they are going to need to get them on the board.

How can you work well on System Design?

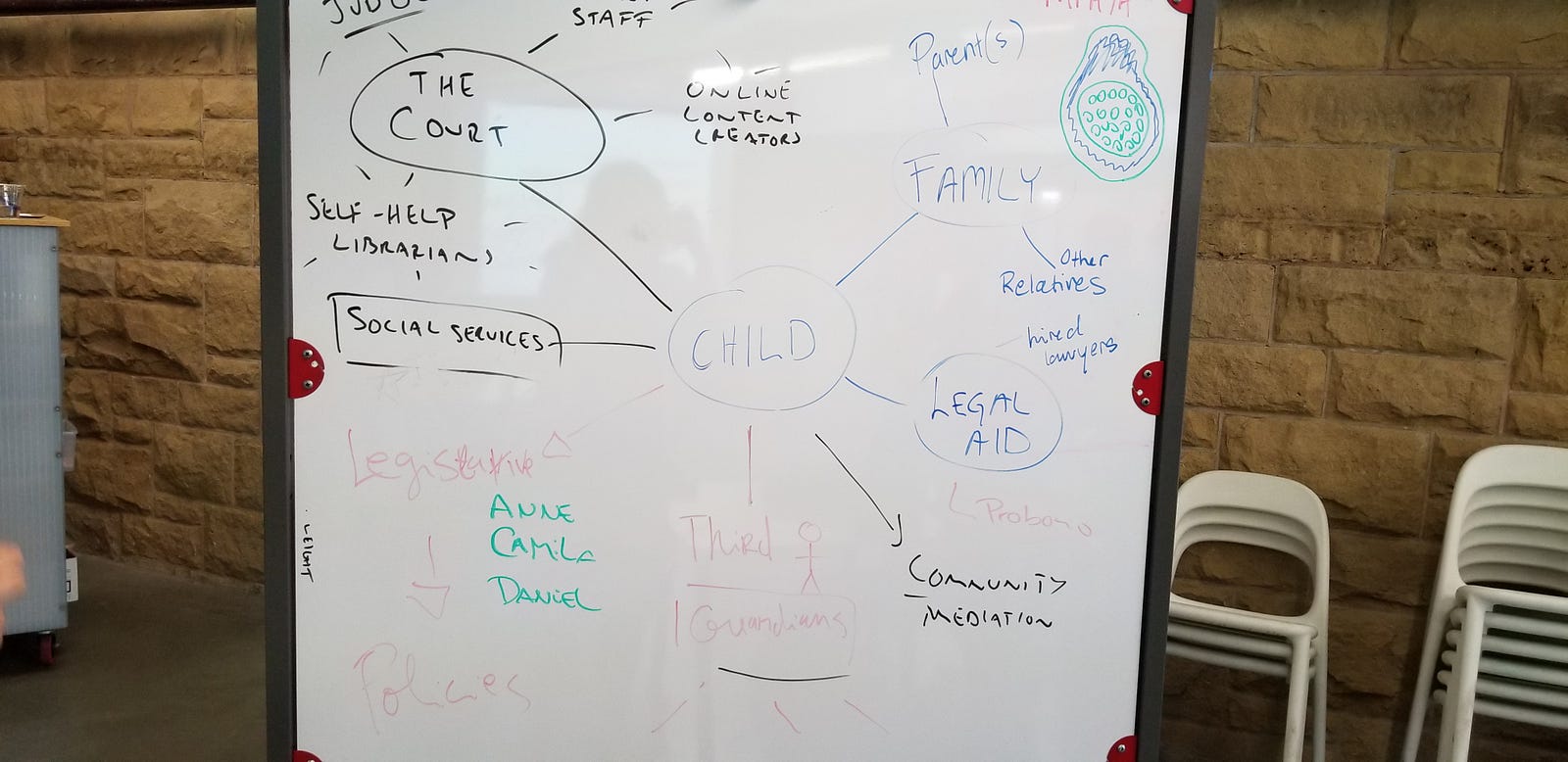

One big lesson they offered: No conference calls — you need to be in the same room together, especially if they are going to tell you anything uncomfortable. You should do some stakeholder mapping exercise with your partner — who are the individual types of humans involved in the decision-making they are talking about, who are the actual humans — it is Mary and Bob to convince to get them on board.

Usually they do a half-day workshop, to cover big topics like ‘what are we doing here’, ‘ have the partners talk about it’, ‘we visualize it as they talk about it’, ‘how will we define success’, ‘what are we going to make’, and the logistics of how we’ll do it.

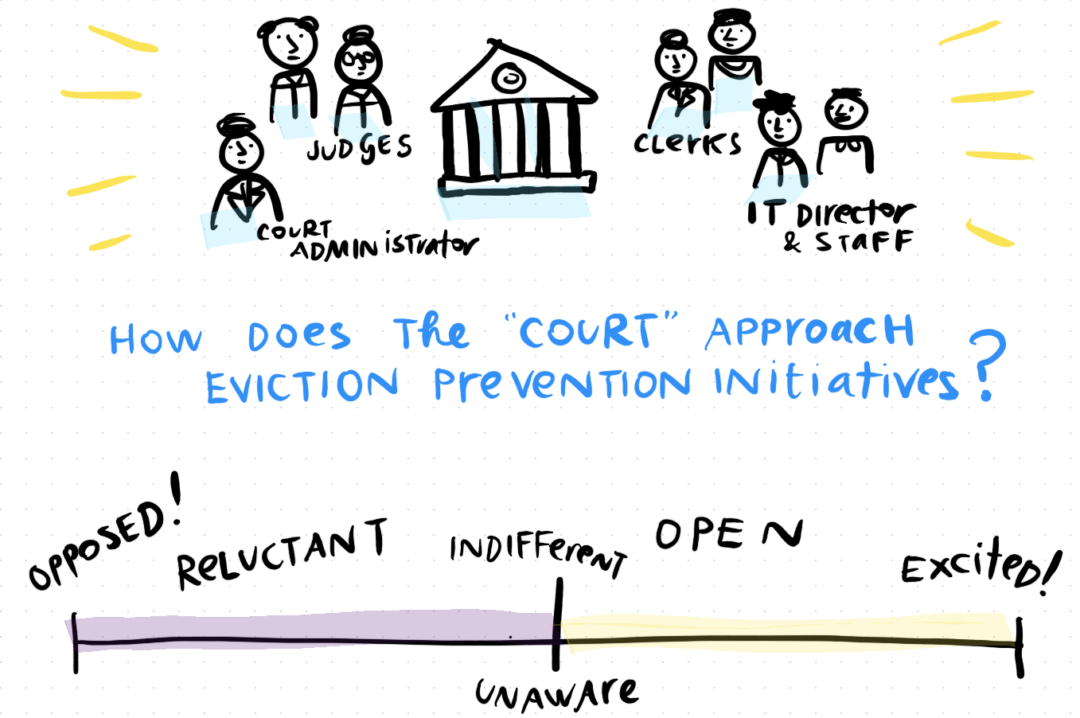

How can you plan for resistance to change?

You can assume there will be people who will resist change. You will never expect people to do what they don’t want to do.

You need to design it for uptake. You need to design what people will embrace because it will benefit them. That’s why to start with observational research — how are people working around the problem, what are the strategies they are already using? Use people’s current behaviors to design for those outcomes. You can amplify the current behaviors, so that they are likely to do what you are expecting.

Can you find a design space where people all want the same thing? You want to find a space where there is alignment.

In addition, you need to see the people in the field, who have capacity and boots-on-the-ground. Who has extra knowledge and assets that you could use in a new program design? You can then activate those resources.

The trickiest population is mid-level management, whose job satisfaction and success aren’t directly affected by the system you’re trying to improve, and who don’t have lived experiences with it. They won’t have as much skin in the game.

What are main challenges to get engagement and involvement

Getting access to people — especially the right people, is more challenging than you would expect. It’s never that easy to get approvals.

The Lab believes in meeting with people in their space, so you are not the ‘expert’ in your ‘focus group’ — but rather in their kitchen, and you are a guest in their home, to learn about their lives. It takes someone whose job it is to arrange those research opportunities, hours on the phone or on text. The logistical challenge is huge, but it is worth it.

Once that happens, then people are incredibly generous with their knowledge and experiences and follow-up. They’re almost always kind and helpful to the process.

If it’s impossible to do substantial, one-on-one engagements — and you have to do ‘Stranger’ research, like a card table in the lobby and intercepting, you can get a lot of knowledge, but you won’t have an ongoing relationship. That may be okay, but know the limits of what you are able to understand about these people.

Often the Lab does rounds of research and testing with different populations, because it’s impossible to get the same people back. You get fresh eyes looking at your work every time. Your design has to work harder.

They always compensate members of the public for their time. But don’t give so much that you are buying their answers — so that you are paying them for what you want to hear.

How to be ethical, and get quality consent?

How do you do informed consent — it is hugely important. Let’s talk about consent procedures. The work designers do is inherently exploitative — we extract people’s experiences and input, then turn around to make something that will not necessarily benefit them directly. We need to be clear on that as our team, and with that knowledge in our team — we are aware of it.

The Lab encourages us to reframe Consent. Instead of consent oriented around protecting your organization — so you won’t be sued, can consent rather be about what the person should expect. So that people know that photos, audios, etc. might be shared out — you are using someone’s face to sell your work, do they understand it? Do they understand where their image might end up? If we take a photo of them, do they know what will happen with it — that it might be on the Internet.

Also, can you aggregate stories, so you are not exposing a single person? We try to get away from anything that could identify a person. We create personas based in research, but they are so aggregated that there is no single person’s life recognizable there.

Especially if a person has less agency — like a child, a person in prison, a person in the hospital, a person with mental illness — we need to be even more transparent with what we’ll do, and what to expect.

During the process, we need to work as hard as we can to strip our own professional authority away — and give the power to the user. Give them final oversight of whatever you’re creating, and ask them for what they would change.

Evaluation and Metrics

The Lab is working on our own evaluation process, because it’s very complicated and it’s hard to determine causality. It takes a long time — how do we actually see changes? It might take 4–5 years after the policy design happened. What do you measure at what point?

When we define a Theory of Change at the outset of our project — we think about evaluation in a few different ways:

- How do we measure the design of the thing?

- How do we measure the experience of the partner?

- How do we measure how policy and organizations change?

The Lab can measure output (kids show up to school; kids aren’t as hungry; people are less poor) for program evaluation. That is often outside their scope of their project partner engagement. They can measure compliance: are staff referring families, are they filling in the form correctly, are families getting set up with a case manager? Those are actions in the program that they can track.

In a past project, they had made lots of design artifacts and strategies, so they could then evaluate: did the partner put posters up, did they table at the school fair, did they send the text messages? Those are our design evaluations, to see if the new system worked. This is formative research, to learn what to design — to see are they working, and how they are not working. The evaluation helps them learn how to redesign.

The Lab is trying to flick multiple levers — not just a single form, they’re doing multiple touch points across a service journey across time, and it’s about human interactions, not just a single form. How do you track systems-level impact? It’s a huge question, that they’re working on.

Many thanks to Chelsea and Shanti for visiting our class, and we are looking forward to seeing more of their work! Read more about the Public Policy Labhere.