There has been a flurry of Legal Design around communicating privacy. Most of the designs concern how to more effectively communicate the policies of technology companies toward the data of their users. The fundamental problem is users’ agreement to the policies by using the services, without a rich understanding of what they are agreeing to through their use. One project that has tried to use graphic & communication design to level this playing field — and communicate companies’ privacy policies with quickness & clarity — came out last year. Privacy Icons is a project under the umbrella of Mozilla, led by designer & technologist Aza Raskin. An article from the NYTimes on the project:

There has been a flurry of Legal Design around communicating privacy. Most of the designs concern how to more effectively communicate the policies of technology companies toward the data of their users. The fundamental problem is users’ agreement to the policies by using the services, without a rich understanding of what they are agreeing to through their use. One project that has tried to use graphic & communication design to level this playing field — and communicate companies’ privacy policies with quickness & clarity — came out last year. Privacy Icons is a project under the umbrella of Mozilla, led by designer & technologist Aza Raskin. An article from the NYTimes on the project:

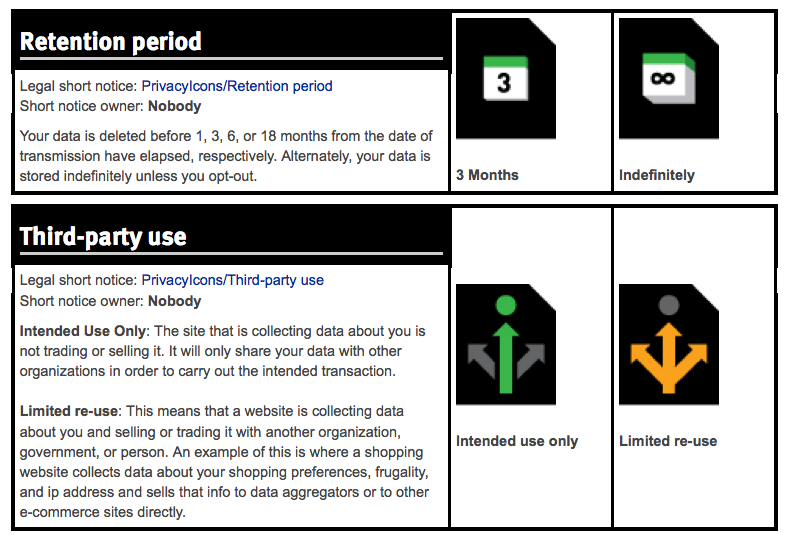

Web site privacy policies are usually long, vague and notoriously neglected by most of us. Or as Alex Fowler, chief privacy officer at Mozilla, put it, “We have long upheld that privacy policies suck.” Now, an experiment is under way to make those privacy policies somewhat more palatable. The idea is to have lawyers and coders muddle through thousands of words of legalese and distill their meaning into a set of graphic icons. In effect, the pros will read those notoriously unreadable policies, so the rest of us don’t have to. The experiment began last Friday in Mozilla headquarters in San Francisco, under aptly dark clouds overhead. It was fueled by chicken-and-bacon sandwiches supplied by disconnect.me, a start-up that offers Web users tools to control how and with whom their personal data is shared. Friday’s assignment was to vet the policies of 1,000 Web sites. If a Web site’s privacy policy suggested that it might sell users’ personal information to third parties, the site was assigned an orange circle with a dollar sign in the middle and an orange arrow pointing up, suggesting caution; if it promised not to sell personal information, it got a green circle. Likewise, if it made personal information available to law enforcement “without proper legal procedure,” it was assigned an orange sheriff’s badge-shaped icon, with an orange arrow pointing up. If it specified how long it retained the data of its users, the number of days was encapsulated in a box; if it did not specify, it was assigned, provocatively, an infinity sign. Web users can install a browser plug-in, available for now only on the Firefox browser made by Mozilla. Once the plug-in is installed, visited Web sites will be marked with a series of icons summing up their privacy terms. The experiment is part of a nascent movement by privacy advocates to educate Internet users about the spread of their personal data online and to offer tools that allow them to control who sees what. It’s aimed for now at Web browsing on desktop computers, but not yet on mobile devices, where it is much harder to scroll through privacy policies. “We are in a model now where no one reads privacy policies,” Mr. Fowler said. “Does icon-ifying them make it of interest to the user? We have a ways to go.” Not even the pros were able to plod through so much jargon, or agree on exactly what it meant. They finished making icons for just 235 Web sites.

The icons Mozilla has established

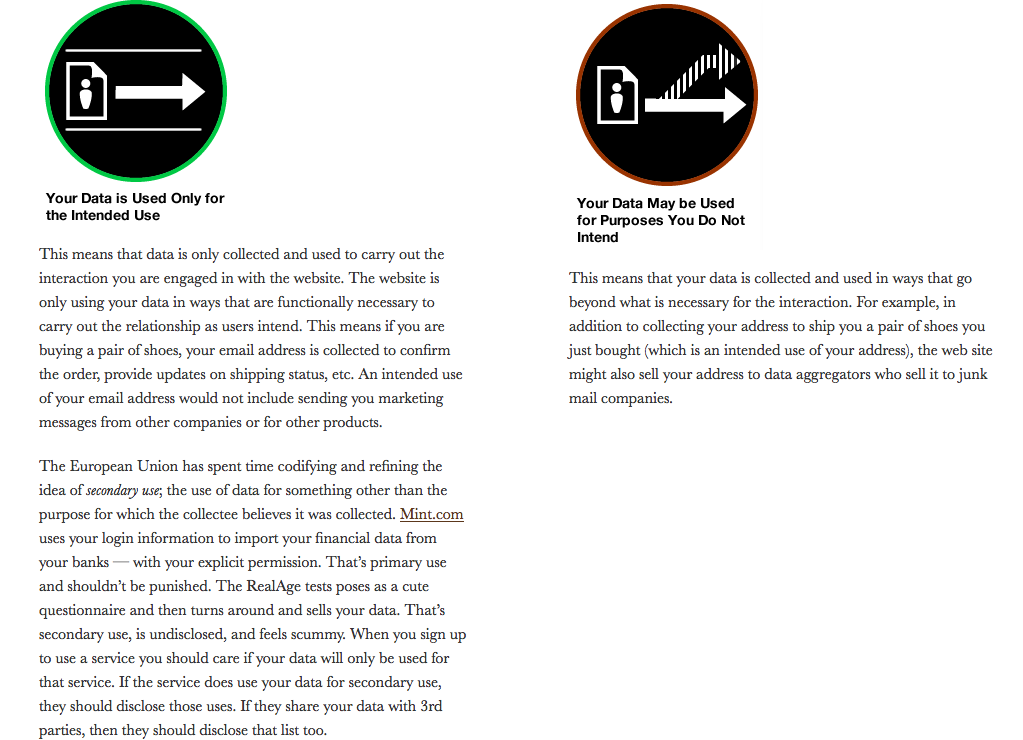

The problem: users need to know how companies intend to use their data—but privacy policies and terms of service are long-winded, complex documents that encapsulate a lot of situation-specific detail. The solution: a set of Privacy Icons to “bolt on to” your existing privacy policy. When you add a Privacy Icon to your privacy policy, you’re essentially saying: “No matter what the rest of this privacy policy says, the following is true and preempts anything else in this document.” Each Privacy Icon makes an iron-clad guarantee about what a company will do with a user’s data. Now, people can understand how their personal data will be transacted, with just a glance. At the same time, companies retain the flexibility needed to create comprehensive, detailed, and meaningful policies. Privacy Icons are legal declarations, written in cooperation with privacy experts and a coalition of industry stakeholders. And soon, they will be machine readable—enabling users to communicate their preferences through trusted agents (like web browsers).

Who Are They For?

For any sites that store user data

For e-commerce sites, advertisers, and social networks, Privacy Icons are a competitive differentiator. Adopting Privacy Icons for your site signals respect for user choice and control, and doing business transparently. There’s an emerging marketplace for personal data, where users exchange information about themselves for online goods and services. But personal data is a currency whose exchange rate is unknown. As users begin to understand the value of their data, the market will reward companies who treat their users transparently and with respect. Over time, the fair value of these exchanges will emerge, and companies who appreciate their customers’ privacy will be rewarded. Differentiation based on privacy matters to users. Think about the large number of sites which vehemently promise to never share your email address when you sign up for their service or mailing list. Those are the kinds of sites, which make up a significant fraction of the web, that should adopt Privacy Icons.

For users who voluntarily share personal data

For users, Privacy Icons are the quickest way to understand the terms by which they offer information about themselves. They help users make informed choices about whether to share their data. Privacy policies are long legalese documents that obfuscate meaning. Nobody reads them because they are indecipherable and obtuse. Yet, these are the documents that tell you what’s going on with your data — how, when, and by whom your information will used. To put it another way, the privacy policy lets you know if some company can make money from information (like selling you email to a spammer). Following in Creative Commons’ footsteps—which used simple visual language to make copyright more understandable—we need to reduce the complexity of privacy policies to an indicator scannable in seconds. Privacy Icons provide a visual language for delving deeper into how our data is used.

FAQ

Q: How do you account for complexity and diversity of policies?

A: We don’t. The icons “bolt-on” to your policy. The Privacy Icon makes an iron-clad guarantee about some portion of how a company treats your data. This method means that without ever having to delve into the details, everyday people can glance at the simple icons atop a privacy to know if and how their data is being used.

Q: Nobody will use the bad icons?

A: Good icons will be competitive advantage. We won’t invest time in “bad” icons, only honest ones.

The Icons Aza Raskin had proposed

via Privacy Icons: Alpha Release « Aza on Design.

Earlier this year, Mozilla convened a privacy workshop that brought together some of the world’s leading thinkers in online privacy. People from the FTC to the EFF were there to answer the question: What attributes of privacy policies and terms of service should people care about? This lead to a proposal presented for the W3C, among other places, which further refined the notion. We are now ready to propose an alpha version of Privacy Icons that takes into account the feedback and participation we’ve received along the way. We’ve simplified the core set dramatically and tightened up the language. While the icons don’t touch on all topics, we do think they significantly move the discussion on privacy, as well as the general level of literacy about privacy, forward. We do not want to let perfection or devotion to taxonomy get in the way of the good. Keep in mind that the target adopters of Privacy Icons are 2nd-tier sites—the sites where differentiation based on privacy matters to their users. Think about the large number of sites which vehemently promise to never share your email address when you sign up for their service or mailing list. Those are the kinds of sites, which make up a significant fraction of the web, that would adopt Privacy Icons. The Icons References to Data mean data that is either personally identifiable (including name, ip address, or email address) or associated with some personally identifiable aspect of your identity (such as correlated with your ip address name, or email address).