via Plea Bargaining: CQR.

Plea Bargaining: Does the widespread practice promote justice?

February 12, 1999, Volume 9 – Issue 6

The vast majority of criminal cases in the United States end not in courtroom trials but in negotiated agreements between prosecutors and defense lawyers. Plea bargaining dates to the 1800s and has often been controversial. Law-and-order advocates say the practice lets criminals get lower sentences, while some defense lawyers and civil libertarians say it coerces defendants to give up their legal rights. Most prosecutors, defense attorneys, and judges, however, say the practice helps produce justice while reducing strains on the court system. Defense lawyers last year cheered a court ruling that would have barred prosecutors from offering leniency in exchange for a defendant’s testimony against accomplices. But prosecutors celebrated last month when the ruling was overturned.

Overview

Sonya Singleton didn’t like the deal offered to her by federal prosecutors in Wichita, Kan. If you implicate your boyfriend in a big drug case, they said, we will let you plead guilty to a minimal money-laundering charge, instead of drug trafficking. The problem, Singleton said, was that she wasn’t a drug dealer.

“She had every opportunity to cut a heck of a good deal,” says her lawyer, John Wachtel. “She refused to cooperate. She said she didn’t know anything [about the drugs] and wasn’t going to lie.”

Singleton’s decision backfired. When the U.S. attorney’s office was unable to nail her boyfriend, it went after her. Prosecutors cut a deal with another suspect in the case, Napolean Douglas, who was offered leniency and a good word to his parole board in return for testifying against Singleton.

Douglas’ testimony helped convict Singleton in 1997 of money-laundering and cocaine-conspiracy charges. Singleton, 24 and pregnant, was sentenced to four years in prison.

In appealing the conviction, Wachtel crafted a bold argument: He contended that the prosecutors’ deal with Douglas violated a federal anti-bribery law that prohibits offering a witness “anything of value” in exchange for testimony. A three-judge panel of the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed.

“Promising something of value to secure truthful testimony is as much prohibited as buying perjured testimony,” Judge Paul Kelly Jr. wrote. “If justice is perverted when a criminal defendant seeks to buy testimony from a witness, it is no less perverted when the government does so.”

The July 1, 1998, ruling cast a shadow over the widespread practice of getting defendants to “turn” against their co-defendants in exchange for leniency — the technique that helped convict Timothy McVeigh in the Oklahoma City bombing. A high-ranking Justice Department lawyer was dispatched to Denver in November to urge the full 10th Circuit court to reverse the decision. Deputy U.S. Solicitor General Michael Dreeben told the 12-judge court that the ruling would “paralyze the ability of federal prosecutors to carry on their business.”

The appeals court agreed. In a 9-3 ruling on Jan. 8, the court said that the so-called anti-gratuity law did not apply to the government. “The decision means prosecutors will be able to continue using the tools they have always used to put criminals behind bars,” the department said in a prepared statement.

Wachtel promises to appeal the ruling. But he faces an uphill battle. The government won similar cases in two other federal appellate courts in December, and the U.S. Supreme Court’s conservative majority has backed law enforcement in most criminal cases over the past two decades.

However the issue is decided, Singleton’s case has helped renew a decades-old debate over plea bargaining — the expedient practice that disposes of most criminal cases in state and federal courts. Originally developed by prosecutors in the 19th century as a way of winning assured convictions, the practice has been attacked in recent years from opposite ends of the political spectrum.

|

Defense lawyers and civil rights and civil liberties organizations, however, contend that prosecutors often abuse the practice, effectively forcing defendants to give up their legal rights by holding multiple charges and the threat of long prison sentences over their heads. “It’s a disincentive to assert a defense,” says Steven Zeidman, an associate professor of criminal law at New York University. “It comes at a cost.”

On balance, however, prosecutors and criminal defense lawyers say plea bargaining dispenses justice fairly and efficiently for defendants, crime victims and the general public.

“It’s not only a fair process but a vital process,” says John Justice, a prosecutor in Chester, S.C., and president of the National District Attorneys’ Association. “The purpose, from a prosecutor’s standpoint, is to get the most favorable result possible without spending the time and resources of having a jury trial.”

“It’s gotten a bad name because it’s misunderstood,” says Larry Pozner, a Denver attorney and president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “It’s an expedited way of getting to justice.”

“It’s fair for the system as a whole,” says Myrna Raeder, a professor at Southwestern University Law School in Los Angeles and chair of the American Bar Association (ABA) section on criminal justice.

The merits of plea bargaining, however, are more apparent at a distance than up close. Visitors to the nation’s criminal courts, especially in major cities, are typically greeted by a confusing scene of lawyers, witnesses, police, jurors and court officers scrambling with crowded dockets. Prosecutors and defense lawyers often engage in hurried last-minute conferences, sometimes in the courtroom, sometimes in hallways, speaking in coded conversation about what a case is “worth” or what it will take to make a case “go away.”

“You have pleas being taken right and left so quickly before the defense lawyer knows anything about the case,” Zeidman says. “In the context of a crowded urban court, it tends to be unseemly.”

Despite the confusion, experts say that within any given jurisdiction the results tend to conform to established patterns.

“Studies of plea bargaining have established that it’s fairly consistent and predictable,” says Samuel Walker, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Nebraska in Omaha and author of a leading history of criminal justice in the United States. “It’s not like a Middle Eastern bazaar where there’s haggling, but more like a supermarket where there are fixed prices.” (continued below)

|

On paper, judges actually impose sentence on a defendant who pleads guilty, but the prosecutor and defense attorney typically negotiate over the sentence during plea bargaining. In the past, plea bargains typically included a specific, agreed-upon sentence for the defendant. The use of sentencing guidelines in federal and state courts since the 1980s, however, has given judges somewhat greater leeway to choose a sentence within a specified range even after the prosecutor and defense attorney have agreed on a plea bargain.

Still, prosecutors play the critical role in the plea-bargaining process by determining what charges to include — and what potential charges to drop — in any agreement. Even under guideline systems, judges rarely go against a prosecutor’s recommendation. And prosecutors sometimes keep their options open by reserving the right to wait until the sentencing hearing to take a position on jail or prison time for the defendant — as Maryland prosecutors did, for example, in successfully urging a judge to send heavyweight prizefighter Mike Tyson to jail this month after his no-contest plea to assault charges in December.

Despite prosecutors’ preponderant influence over the plea-bargaining process, some district attorneys join law-and-order critics in denouncing the practice.

A few prosecutors — including district attorneys in two New York City boroughs — have adopted policies aimed at curbing plea bargaining. Critics say the policies — prohibiting plea bargaining after but not before indictment — put undue pressure on defendants and their lawyers to settle a case before a defense can be investigated and prepared.

Defense lawyers say plea bargaining has also become more difficult because of tough sentencing laws passed by Congress and many states. In particular, they complain that the federal Sentencing Guidelines — which took effect in 1987 — have shifted too much bargaining power to federal prosecutors.

The laws have not been an unmixed blessing for prosecutors, however. For example, a widely noted California law that imposes long prison sentences on three-time offenders has resulted in fewer plea bargains and more trials — straining court capacity in some places.

Some crime victims complain about the bargains that prosecutors and defense lawyers strike. The partner of an Atlanta policeman slain in 1981, for example, sharply protested a plea bargain in late December giving a life sentence to his killer, who had won a retrial in the case after having previously been sentenced to death. “I think it’s a total breakdown of the judicial system,” said the officer, Greg Thames. Prosecutors said they negotiated the plea because of witness problems.

Although legal experts say the widespread use of plea bargaining will continue, so will the debate over its fairness. Here are some of the questions about the practice being asked:

Does plea bargaining undermine effective prosecution of criminals?

Three white Chicago youths were charged in 1997 with savagely beating a black teenager in their neighborhood. One of the three, Frank Caruso Jr., was sentenced last fall to eight years in prison. But Victor Jasas and Michael Kwidzinski pleaded guilty to reduced charges and were sentenced to probation and community service.

Wanda McMurray, whose son was brain-damaged by the beating, thought that the plea bargain made no sense. “The other two guys pleaded, saying that they did it,” McMurray said. “So, why didn’t they go to jail? It’s stupidity.”

The episode reflects the recurring criticism that plea bargaining harms law enforcement. The practice first gained significant public attention in the United States in the 1920s when civic groups in Cleveland and Chicago charged that the practice hampered law enforcement against street crime as well as organized-crime syndicates. Much of the criticism since then has sounded the same theme: that serious criminals are given reduced sentences or escape prison altogether and get back on the streets to commit more crimes.

Numerous studies confirm that defendants who plead guilty generally receive lower sentences than those convicted after trial. A 1987 study estimated that sentences imposed in federal courts after guilty pleas were 30-40 percent as long as typical sentences imposed after trial.

Nonetheless, most criminal-justice experts say that plea bargaining generally results in just sentences while ensuring that defendants are convicted of some offense and avoiding undue burdens on prosecutors and courts.

“One of the myths is that you have all these offenders getting off easy,” says Walker at the University of Nebraska. “All of the research indicates that that is not the case.”

“The prosecutor gains two clear benefits — the certainty of victory and the savings of time and energy by not having to go to trial,” says George Fisher, a professor at Stanford Law School and a former state prosecutor in Massachusetts. “The public benefits because cases go through the system much more cheaply and quickly than they otherwise would.”

In addition, says South Carolina prosecutor Justice, plea-bargained sentences usually are “in the ballpark” with sentences imposed after trial. Defendants “generally get the same result they would have gotten anyway,” he says.

The law-enforcement benefits from plea bargaining are often more apparent to the criminal-justice community than to the general public.

Prosecutors stress the importance of an assured conviction, especially when the evidence is shaky. In the Chicago case, for example, prosecutors said their cases against Kwidzinski and Jasas had significant witness problems. “One witness was murdered, another witness has been missing, a third witness had total lack of recall on the witness stand . . . and Lenard Clark, the victim, had no recollection of the event,” prosecutor Richard Devine told CNN.

Fisher also stresses that plea bargains allow for quicker disposition of cases. “Speed is important,” he explains. “During the time we’re waiting for a free courtroom, the defendant may be free on the streets, and in any event the evidence is getting weaker and weaker.”

The law-and-order critique of plea bargaining is all the weaker today, some experts say, because of the trend toward longer prison terms. “Clearly, sentencing has gotten much more punitive,” says Southwestern Law School’s Raeder. “The plea bargains wind up calling for a much lengthier sentence simply because the prosecution has so much more leverage.”

Despite the general acceptance of plea bargaining, a few prosecutors have their doubts. In New York, Bronx County District Attorney Robert Johnson bars plea bargaining in felony cases after indictment. In announcing the 1992 policy, Johnson said the move would mean that “many robbers, rapists, burglars and drug dealers will have to go to jail.”

But New York University’s Zeidman, who works with indigent criminal defendants, says that prosecutors would not plea bargain if they really thought it hurt law enforcement. “Since 90 percent [of criminal cases] are resolved by these sorts of pleas, the proof is in the pudding,” he says. “The proof is that it is not detrimental.”

Is plea bargaining unfair to criminal defendants?

California general contractor Gary Costanza was one of three men charged with murder at a San Jose strip club in 1997. Although he denied any responsibility for the beating death of entertainer Kevin Sullivan, he nonetheless pleaded guilty to conspiracy charges and drew a three-year prison sentence.

“He vehemently denied any guilt,” said his attorney, Bud Landreth. “The sole reason for the plea was that he couldn’t take a chance on the life sentence. It was almost like a coerced plea.”

In contrast to most plea bargains, Costanza did not agree to testify in the trial of his co-defendants, David Kuzinich and Steve Tausan. And last month, in a surprising verdict, a jury acquitted them of all charges.

When Landreth vowed to file a motion for Costanza to withdraw his plea, assistant Santa Clara County District Attorney Dave Davies initially rejected the suggestion. “A plea bargain is a plea bargain,” he said. In a Jan. 15 court hearing, however, Davies agreed to probation for Costanza, who walked out of jail later that day after 15 months behind bars.

Many defendants enter guilty pleas for the same reason Costanza did — to avoid the risk of a long prison sentence. But only a few simultaneously deny their guilt, as Costanza did, in what’s known as an “Alford” plea, after a 1970 Supreme Court decision. Most defendants admit their guilt in scripted colloquies with judges designed to establish that the defendant is entering the guilty plea “voluntarily” and is actually guilty of the offenses covered by the plea.

The supposed voluntariness of most pleas is a legal fiction. “You have to have nerves of steel to go to trial,” Zeidman says. But prosecutors deny that they abuse the practice. “I won’t bargain a case unless I can justify the charge on the facts to the jury,” says South Carolina prosecutor Justice.

The defendant who pleads guilty gives up an array of rights fundamental to American justice: the right to require the government to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt, the right to cross-examine witnesses, the right to present a defense and the right to have a jury determine guilt or innocence. The earliest court cases in the United States dealing with plea bargaining reflected a concern about putting undue pressure on defendants to waive their rights, and courts in the 1950s and ’60s established some rules aimed at policing the practice.

Still, there is little doubt that in the typical criminal case the prosecutor begins any bargaining with what former prosecutor Fisher calls “unfair advantages.”

“The defendant may be badly represented or badly informed, because the prosecution hasn’t disclosed all the information that it may have,” Fisher says. “A defendant who belongs to a minority racial group might realistically judge his chance of acquittal to be less than the evidence would justify. And then, of course, prosecutors can overcharge and thereby increase their bargaining power past what it should be.”

Despite those advantages for the prosecution, defense lawyers stop short of any general critique of the fairness of the practice. “The horror stories are aberrations,” says Denver attorney Pozner. “People don’t get charged with something big and plead to something little. That’s not what happens.”

Unfair to defendants? “No, I wouldn’t say that,” Zeidman answers. “They get a guaranteed sentence, and they minimize their exposure to a potentially more serious sentence.”

Defense lawyers and many legal experts do agree, though, that federal prosecutors have gained additional bargaining power since the creation of federal Sentencing Guidelines in 1987.

The guidelines require federal prosecutors to base their charges on a defendant’s “actual conduct,” and judges are supposed to calculate sentences according to the complex formulas established by the U.S. Sentencing Commission. “The prosecutor has a substantial amount of discretion, and the judge has very little discretion,” says Steven M. Cohen, former head of the gang enforcement unit of the U.S. Attorney’s office in New York City.

Judges have only limited authority to make “downward departures” from the guideline-calculated sentence. The most common reason for such a reduction is what the guidelines call a “defendant’s substantial assistance in the investigation and prosecution” of others.

There is disagreement over the roles played by prosecutor and judge in reducing sentences for a defendant’s assistance. Yale University law Professor Kate Stith and federal appeals Judge Jose A. Cabranes note in their 1998 book on the sentencing guidelines that prosecutors are required to request a downward departure in such cases. But Cohen stresses that the judge retains the final decision. “It’s not the prosecutors who are deciding, it’s the judges,” he says. “That’s a fairly reasonable approach to dealing with cooperating witnesses.”

However the decision-making power is allocated, experts do agree that the practice of reducing sentences for “substantial assistance” is increasing — underlining the importance of the issues raised in the Singleton case. “It used to be the rare case where a defendant would turn into an informer as part of a plea bargain,” Raeder says. “The Sentencing Guidelines have made what was a rarity into the standard coin of the realm.”

Should plea bargaining be abolished or significantly curtailed?

In 1989, U.S. Attorney General Richard Thornburgh ordered federal prosecutors around the country to limit plea bargaining. Prosecutors, the so-called Thornburgh bluesheet stated, “should initially charge the most serious, readily provable offense or offenses” and should not abandon charges “to arrive at a bargain that fails to reflect the seriousness of the defendant’s conduct.”

The directive apparently had only limited effect. In one study coauthored by a member of the Sentencing Commission, federal prosecutors admitted to trying to circumvent the guidelines in one-fourth of the cases resolved by pleas.  And Thornburgh’s successor, Janet Reno, issued a revised directive in 1993 stating that the sentencing guidelines were “not incompatible with selecting charges or entering into plea agreements on the basis of an individualized assessment of” the case.

And Thornburgh’s successor, Janet Reno, issued a revised directive in 1993 stating that the sentencing guidelines were “not incompatible with selecting charges or entering into plea agreements on the basis of an individualized assessment of” the case.

The Justice Department’s policy flip-flop reflects the difficulties faced by prosecutors and lawmakers in eliminating or restricting plea bargaining. Nonetheless, several states have tried. A California law, for example, bars plea bargaining for a laundry list of “serious” felonies as well as firearm offenses and drunken driving.  In addition, prosecutors in some jurisdictions claim to have abolished plea bargaining, at least at certain stages of a criminal case.

In addition, prosecutors in some jurisdictions claim to have abolished plea bargaining, at least at certain stages of a criminal case.

But defense lawyers say the policy puts unfair pressure on defendants at an early stage. “It’s a now-or-never proposition,” says Stephen S. Singer, a former president of the Queens County Bar Association. “They scare the bejesus out of these people by saying there will never be another opportunity to negotiate a plea.”

Other critics say that efforts to abolish or restrict plea bargaining simply mask the practice rather than change it. “The most that is ever accomplished is that the plea bargaining shifts from a visible stage of the process to a more covert stage,” says former prosecutor Fisher.

“Once charges are brought, it’s quite clear when a prosecutor drops a charge in response to a plea,” Fisher explains. “But if the district attorney bans that practice, prosecutors can learn to consult with defense counsel before charges are brought and secure a plea arrangement then. The form of the plea becomes, ‘I will seek only these charges if you will promise that your client will plead guilty.’ ”

Academics voiced similar doubts about the feasibility of abolishing plea bargaining when the idea was endorsed by a presidential commission in 1973 and adopted by a number of prosecutors. Over the past decade, some supporters of the federal sentencing guidelines have said their effect would be to limit plea bargaining by U.S. prosecutors, but those claims have also been met with substantial skepticism.

The guidelines do include provisions aimed at ensuring that plea agreements reflect a defendant’s “real offense” and stipulating that judges accept a plea only if the charges “reflect the seriousness of the actual offense behavior.”

But, in their recent book evaluating the guidelines, Stith and Cabranes call the directives “simplistic” and doubt their impact on plea-bargaining practices. The guidelines, they write, “drive the process of adjustment underground and hide from observers the decisions that actually shape a sentence.”

The Bronx and Queens district attorneys say their early-deadline, plea-bargaining policies help save money and manpower and limit defendants’ ability to drag out criminal cases. But they acknowledge that the policies do not completely prohibit plea bargaining and that plea agreements are sometimes permitted even after indictment.

As for complete abolition of plea bargaining, the idea is even doubted by a leading victims’-rights group. “If plea bargaining were removed entirely or severely limited,” says Beatty of the National Center for Victims of Crime, “the judicial outcomes may in the long run frustrate the ends and purposes of justice that victims would prefer.”

Let’s Make a Deal

Plea bargaining has existed in some form since the earliest days of American criminal justice. Some courts issued rulings frowning on the practice in the late 1800s, and more visible controversies arose in the 1920s. But the true extent of plea bargaining went largely unrecognized — even by legal experts — until the 1960s or so.

Scholars have found hints of plea bargaining in Colonial times. A study of 17th-century New York courts found that one-third of all criminal cases vanished from the records; even if many were dismissed for lack of evidence, says the University of Nebraska’s Walker, the evidence suggests the existence of “something” like plea bargaining.  A study of Boston’s lower criminal courts found a sharp rise in guilty pleas through the first half of the 19th century; by 1850, the study found, nearly two-thirds of cases for violating city ordinances and just over half of public-drunkenness cases were disposed of by guilty pleas.

A study of Boston’s lower criminal courts found a sharp rise in guilty pleas through the first half of the 19th century; by 1850, the study found, nearly two-thirds of cases for violating city ordinances and just over half of public-drunkenness cases were disposed of by guilty pleas.

By the late 19th century, the evidence of plea bargaining is “unmistakable,” according to Lawrence Friedman, a professor at Stanford Law School and one of the country’s leading legal historians. In his study of criminal cases in Alameda County (Oakland), Calif., from 1880 to 1910, Friedman found that 14 percent of all defendants changed their pleas from not guilty to guilty; half of those defendants pleaded to lesser or fewer charges, Friedman said — “unmistakably the sign of a deal.” Friedman also found that about one-third of the prisoners at California’s Folsom prison in 1880 who had pleaded guilty said they did so in order to “mitigate the penalty.”

Some 19th-century judges criticized the incipient practice of plea bargaining, according to scholar Hedieh Nasheri.  In the first-known American appellate decision on a guilty plea, Massachusetts’ highest court in 1804 approved a black defendant’s admission to a charge of raping a white teenager only after first ordering a hearing to determine whether there had been “any tampering with him, either by promises, persuasion, or hopes of pardon if he would plead guilty.”

In the first-known American appellate decision on a guilty plea, Massachusetts’ highest court in 1804 approved a black defendant’s admission to a charge of raping a white teenager only after first ordering a hearing to determine whether there had been “any tampering with him, either by promises, persuasion, or hopes of pardon if he would plead guilty.”

These occasional judicial criticisms had no effect in slowing the advance of plea bargaining in the late 1800s. One reason for the growing practice may have been an increase in criminal prosecutions. In Cuyahoga County (Cleveland), Ohio, the number of prosecutions increased eightfold from 1863 to 1900 while the number of prosecutors only went up from one to three.  But both Friedman and Nasheri stress that the growth of plea bargaining reflected and paralleled a maturing process within law enforcement. It was, as Friedman says, “part of the trend to professionalize and rationalize criminal justice.” Courts lost their dominant role in criminal justice, Nasheri adds, as professional police replaced the citizen nightwatch, and prosecutors took greater control of charging decisions and displaced the jury in deciding punishment.

But both Friedman and Nasheri stress that the growth of plea bargaining reflected and paralleled a maturing process within law enforcement. It was, as Friedman says, “part of the trend to professionalize and rationalize criminal justice.” Courts lost their dominant role in criminal justice, Nasheri adds, as professional police replaced the citizen nightwatch, and prosecutors took greater control of charging decisions and displaced the jury in deciding punishment.

Whatever the cause, plea bargaining had become a commonplace practice in many court systems by the turn of the century. In New York County, for example, the number of felony convictions by guilty pleas was three times the number of convictions by judge or jury. “Ordinarily, in a full court day there will occur from two to four complete trials, while an equal number of pleas may be taken,” a lawyer wrote in 1906. “Sometimes 150 cases will be got rid of by trial or plea in a single term in one part of General Sessions alone.”

Gaining Acceptance

In the 20th century, plea bargaining became the main way of disposing of criminal cases in urban and rural areas alike. While the practice attracted more criticism, it also gained greater acceptance, even from the U.S. Supreme Court.

The preponderant use of plea bargaining was documented in a 1928 study commissioned by a Cleveland civic group. It found that in the 1920s guilty pleas accounted for 86 percent of all felony convictions in Cleveland and similar percentages in New York and Chicago, as well as 91 percent in rural upstate New York.

The American Law Institute, a court-reform group, said in a 1934 study of the federal courts that plea bargaining was “responsible for the prompt and efficient disposition of business.” It was “doubtful if the system could operate without it,” the ALI concluded.

As plea bargaining came to be more explicitly acknowledged, courts turned away from trying to halt the practice and instead sought to control it. In 1958, for example, New York’s highest court ruled that a defendant was not obliged to stand by a guilty plea coerced by threats of additional punishment.

“[T]here is no bargain if the defendant is told that, if he does not plead guilty, he will suffer consequences that would otherwise not be visited upon him,” the court declared.

The efforts to regulate plea bargaining advanced in the 1960s. A national crime commission appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson called in 1965 for greater openness. Plea agreements, the commission said, should include a statement of the facts of the case, the initial positions of the prosecution and the defense, and the reasons for the agreed-upon disposition; and the agreement should be “probed by judicial questioning.”

The American Bar Association adopted standards for plea bargaining in 1968 somewhat along those lines. And in 1969 the federal courts adopted Rule 11(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which required a judge, before accepting a guilty plea, to “personally” address the defendant and determine that the plea “is made voluntarily with understanding of the nature of the charge and the consequences of the plea.”

Supreme Court Rulings

The Supreme Court itself validated regulated plea bargaining in a series of cases as the liberal Warren Court gave way to the more conservative Burger Court.  In one, Chief Justice Earl Warren spoke for the court in 1969 in reversing a conviction because the trial judge had failed to comply with Rule 11(e)’s requirement to make sure that the defendant understood the nature of the charge against him, the rights he was giving up, and the penalties he faced (McCarthy v. United States). Later that year, the court made clear that the Constitution itself — not just Rule 11(e) — required that a judge ensure that a plea of guilty was both intelligent and voluntary (Boynkin v. Alabama).

In one, Chief Justice Earl Warren spoke for the court in 1969 in reversing a conviction because the trial judge had failed to comply with Rule 11(e)’s requirement to make sure that the defendant understood the nature of the charge against him, the rights he was giving up, and the penalties he faced (McCarthy v. United States). Later that year, the court made clear that the Constitution itself — not just Rule 11(e) — required that a judge ensure that a plea of guilty was both intelligent and voluntary (Boynkin v. Alabama).

The next year, however, the court — now led by Chief Justice Warren Burger — issued four rulings that narrowly defined the “voluntary and intelligent” requirement. In one, the court upheld the second-degree murder conviction of a defendant who stated in court, “I ain’t shot no man,” but was pleading guilty “because they said if I didn’t they would gas me for it.” A defendant could “voluntarily, knowingly, and understandingly consent to the imposition of a sentence,” the court said in North Carolina v. Alford, “even if he is unable or unwilling to admit his participation in the acts constituting the crime.”

Finally, in 1971 the court put its stamp of approval most forcefully on plea bargaining. The ruling in Santobello v. New York threw out a defendant’s conviction because the prosecution had gone back on a promise to recommend a minimum sentence if the defendant pleaded guilty. Writing for the court, Burger said that a prosecutor’s promise “must be fulfilled” if it induced the defendant to plead guilty. In reaching that conclusion, Burger explicitly endorsed plea bargaining as “an essential component of the administration of justice.” Without it, Burger said, “the States and the Federal Government would need to multiply by many times the number of judges and court facilities.”

Ironically, the Supreme Court’s embrace of plea bargaining did not settle the debate over the practice. Instead, the law-and-order mood that had been gaining ground since the late 1960s led to an increase in public opposition to plea bargaining and calls to abolish or significantly curtail the practice.

Under Attack

Only eight years after a presidential commission endorsed plea bargaining, a new study group appointed by President Richard M. Nixon called in 1973 for its abolition. Over the next decade, prosecutors in several jurisdictions vowed to do just that. Both then and now, skeptics doubted the real impact of the supposed bans on plea bargaining. In any event, the practice survived virtually unchanged in the vast majority of state and federal jurisdictions.

The call to abolish plea bargaining was included in a 1973 report by the National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice Standards and Goals: “As soon as possible, but in no event later than 1978, negotiations between prosecutors and defendants . . . concerning concessions to be made in return for pleading guilty should be prohibited.”  In the same year, however, the National District Attorneys’ Association called the abolition of plea bargaining “unrealistic.” Plea bargaining, the prosecutors said, “is presently an absolute necessity.”

In the same year, however, the National District Attorneys’ Association called the abolition of plea bargaining “unrealistic.” Plea bargaining, the prosecutors said, “is presently an absolute necessity.”

One prominent prosecutor had already adopted a no-plea-bargaining policy. Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., who was Philadelphia district attorney from 1969-1973, gained national attention for banning plea bargaining. But author Charles Silberman concluded in 1978 that Specter merely shifted the terms of the negotiations between prosecutors and defense lawyers. Defendants who agreed to be tried by a judge rather than a jury were given implied sentencing concessions, Silberman said, and the judges assigned to bench trials were usually known as relatively lenient sentencers anyway.

New York’s legislature, at the urging of Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, enacted a limited ban on plea bargaining in 1973 as part of a get-tough-on-drugs law. The act called for stiff, mandatory penalties for drug offenses and prohibited plea bargaining for some of the offenses. The penalties, however, proved to be so severe that many police and prosecutors apparently avoided bringing charges under the specified offense. By 1979, the state legislature substantially revised the act.

The most ambitious of the experiments came in Alaska, which abolished plea bargaining statewide in 1975. Despite initial criticism by judges and defense attorneys, researchers concluded in 1980 that the ban had been largely effective without resulting in a sharp increase in the number of trials. But they found that the ban raised sentences on lesser offenses more than it raised them for serious crimes.

Other experiments, however, produced results that defenders of plea bargaining had predicted. In El Paso, Texas, two years after a ban on plea bargaining in felony cases was adopted in 1975, courts faced an “unprecedented backlog,” according to researchers.

As the national crime commission’s 1978 deadline to abolish plea bargaining came and went, the practice had clearly survived. Abolishing plea bargaining “is more easily said than done,” Silberman wrote then.  Fifteen years later, legal historian Friedman noted that efforts to restrict plea bargaining were “decidedly mixed.” Plea bargaining, he wrote, “seemed to have nine lives.”

Fifteen years later, legal historian Friedman noted that efforts to restrict plea bargaining were “decidedly mixed.” Plea bargaining, he wrote, “seemed to have nine lives.”

Sentencing Guidelines

Concerns about plea bargaining receded in the 1980s and ’90s as Congress and the states turned to a new issue: sentencing reform. Lawmakers sought to eliminate sentencing disparities by enacting guidelines for judges to use in setting prison terms. Many of the schemes also sought to reduce parole boards’ discretion to release inmates before the completion of their sentences.

Over time, Congress and many state legislatures made the new sentencing systems more stringent by prescribing mandatory minimum sentences for certain offenses and, in some states, providing for very long sentences for repeat offenders. Those changes reduced the incentives for defendants to plea bargain and gave prosecutors greater leverage in negotiating plea agreements.

Congress enacted a new federal sentencing scheme in 1984 as part of an omnibus crime-control measure.  The law created a seven-member federal Sentencing Commission charged with promulgating sentencing guidelines to eliminate “unwanted sentencing disparity.” The guidelines, which took effect in 1987, set ranges of punishments for federal offenses and directed judges to sentence defendants within the ranges based on such factors as the defendant’s prior record and the seriousness of the offense.

The law created a seven-member federal Sentencing Commission charged with promulgating sentencing guidelines to eliminate “unwanted sentencing disparity.” The guidelines, which took effect in 1987, set ranges of punishments for federal offenses and directed judges to sentence defendants within the ranges based on such factors as the defendant’s prior record and the seriousness of the offense.

Judges could depart from the guidelines, but they had to explain their reasons. One specific justification for a downward departure was a defendant’s “substantial assistance” in apprehending and prosecuting other offenders. Many states enacted similar schemes, although most of the state laws made the guidelines advisory rather than mandatory.

Many judges criticized the sentencing guidelines as too rigid and too complex. In addition, some judges discounted the predictions of some guideline supporters that the new schemes would reduce the importance of plea bargaining. Plea bargaining “would not be eliminated,” Lois Forer, a judge in Philadelphia, wrote in 1980. “It would take place behind the closed doors of the prosecutor’s office rather than in open court.”

Criticism of the guidelines intensified in the 1990s as lawmakers responded to anti-crime sentiment by grafting on mandatory minimums for certain crimes, such as drug offenses and crimes committed with firearms, and longer sentences for repeat offenders. The most stringent was California’s “three-strike” law: The measure calls for 25 years to life imprisonment for a defendant convicted of a violent felony after two prior serious felony convictions.

California’s law appears to have sharply increased the number of criminal cases taken to trial rather than settled through a plea bargain. About one-fourth of the cases in Los Angeles County covered by the law during its first 26 months on the books went to trial, compared with the more traditional percentage of criminal cases tried: about 4-5 percent. Even so, about 45 percent of the three-strikes cases were plea-bargained — despite a stated policy in the prosecutor’s office of negotiating agreements only in “exceptional circumstances.”

With the addition of the mandatory penalty provisions, Forer renewed her critique of the new sentencing schemes in a 1994 book. “The only official who has authority under these laws to decide what the penalty will be is the prosecutor, who can drop more serious charges and proceed on the less serious ones,” she wrote. “Discretion has been transferred from the judge to the prosecutor. The public does not know what ‘deal’ has been made or the basis for the decision.”

Many defense lawyers and at least some former prosecutors joined in criticizing the guidelines system. But Congress has shown no inclination to overhaul the system. “Whether people like it or not, we’re now operating in the world of sentencing guidelines,” says former prosecutor Cohen.

Challenging the ‘Snitch’

Last July, U.S. prosecutors in Denver said they were dropping armed robbery charges against three men charged in a pair of armed robberies in Colorado Springs one year earlier. Prosecutors said the case depended on the plea-bargained testimony of two accomplices — testimony that the ruling in the case of Sonya Singleton a week earlier now prohibited the government from using.

The Singleton ruling applied only in the states in the 10th Circuit: Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming. But federal prosecutors around the country were worrying about the ruling’s effect on their cases. In fact, two lower federal courts in Florida and Tennessee issued similar rulings. And the issue was pending in at least three other federal circuits.

The 10th Circuit blunted the immediate effect of the ruling just 11 days later by issuing a stay and agreeing to rehear the case before the full 12-judge court in November. Anticipating a possible reversal, the chief federal district court judge in Denver persuaded prosecutors to withdraw their motion to dismiss the Colorado Springs robbery case.

The arguments before the 10th Circuit appeals court on Nov. 17 showed the judges divided. The three judges who signed the original opinion stoutly defended their position, but several of the others sharply challenged Singleton’s attorney, Wachtel, as he sought to preserve his victory.

Wachtel contended that the anti-gratuity statute meant exactly what it said: Government lawyers had clearly offered Douglas “something of value” — leniency — in return for his testimony against Singleton. But judges challenged his “plain meaning” interpretation of the law. “The common law practice must be incorporated into one’s understanding of the statute,” Judge Mary Briscoe said.

Deputy Solicitor General Dreeben emphasized the long acceptance of the practice in his brief and argument. The appeals court ruling, if upheld, would “make criminals of all federal judges who have approved a plea bargain making concessions for testimony,” he said in his brief.

But the three judges on the original panel sharply challenged him on the effects of the decision. They picked up Wachtel’s argument that the government could get around the statute — and reduce a defendant’s motivation to lie on the stand — by sentencing him before he testifies against his co-defendant rather than waiting until afterward.

Dreeben demurred. “Should the plea agreement fall apart,” he said, “the government will have no recourse.”

The debate over the statute continued in the legal community as the judges pondered their decision. Former federal prosecutors sharply denounced the ruling, agreeing with the Justice Department that the decision would make it impossible to prosecute many organized-crime and white-collar crime cases. Joseph DiGenova, a former U.S. attorney in Washington, D.C., called the decision “bizarre.” “This is simply not bribery or any inducement other than what is properly recognized by the law,” he said.

But defense lawyers insisted the government’s use of “snitch testimony” invited abuse. ‘If a defense lawyer went up and said, “I’ll give you $10,000, but first you have to have information favorable to my client, there would be a lot of defense witnesses,” defense lawyer Pozner said. “We don’t let defense lawyers do that. But the government is allowed to engage in one-sided tactics that are likely to produce perjured testimony and then at the end get to decide whether it’s happy” and will keep its part of the bargain.

When the court issued its decision on Jan. 8, the government won a decisive victory. The three judges on the original panel stuck to their position, but the nine other judges sided with the government.

The anti-gratuity statute simply did not apply to the government’s practice of offering leniency to defendants for testifying against others, Judge John Porfilio wrote for the majority. “[A]ny reading of [the law] that would restrict the exercise of this power is surely a diminution of sovereignty not countenanced in our jurisprudence,” Porfilio said. In addition, the judge reasoned, Congress would have used “clear, unmistakable and unarguable language” if it had intended to “overturn this ingrained aspect of American legal culture.”

The Justice Department declared itself “pleased” with the decision. “Offering leniency in exchange for truthful testimony is a longstanding, important aspect of the legal system,” the government said. “The Court of Appeals today reaffirmed the lawfulness of that practice.”

For his part, Wachtel was guarded in his comments. “I respectfully disagree,” he said. “Just because I lost doesn’t mean I’m wrong.” He said Singleton, who is being held in a federal prison in Texas, was “disappointed” with the ruling. But he noted that she is due to be released sometime this spring.

Wachtel plans to seek U.S. Supreme Court review of the decision, but review appears unlikely. Two other federal appeals courts also backed the government’s position, and the high court often takes up cases only if there is a disagreement between federal circuits.

Grading the Guidelines

As Congress worked on creating the sentencing-guideline system in the early 1980s, some lawmakers worried that the new rules would — as the Senate committee report put it — “simply shift discretion from sentencing judges to prosecutors.”  To guard against the possibility of abuse, Congress inserted a provision directing the new Sentencing Commission to issue “policy statements” for judges to use in deciding whether to accept a plea agreement.“

To guard against the possibility of abuse, Congress inserted a provision directing the new Sentencing Commission to issue “policy statements” for judges to use in deciding whether to accept a plea agreement.“

More than a decade later, the commission’s policy statements offer only limited guidance to federal judges. The policy statements reinforce and add to earlier provisions of the federal Rules of Criminal Procedure requiring certain formalities in plea agreements. They stress that the judge has the final say in deciding whether to accept a plea agreement and in determining the defendant’s sentence under the guidelines.

As for substantive policy guidance, however, the commission has told judges only that plea negotiations must “promote the statutory purposes of sentencing” listed in the law and “do not perpetuate unwarranted sentencing disparity.”

“Congress stepped aside on the difficult issue of plea bargaining,” says Marc Miller, a professor at Emory University School of Law and one-time editor of the Federal Sentencing Reporter. “Then the commission stepped aside, too.”

Miller notes that there is little evidence that judges have exercised their power to reject plea agreements. In any event, the guidelines tend to strengthen the prosecutor’s position in plea bargaining by directing judges to ensure that any sentence take account of all of a defendant’s “relevant conduct” whether or not it is encompassed within the charges included in a guilty plea. And, to a limited extent, the guidelines encourage guilty pleas by giving a judge discretion to treat such an admission as “acceptance of responsibility,” justifying a downward departure from a guideline-calculated sentence.

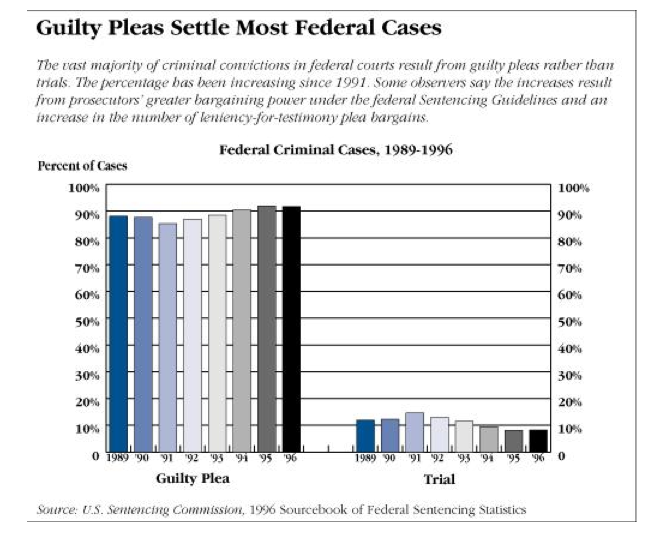

The effect appears to have been to increase somewhat the percentage of cases ended in federal courts by guilty pleas, according to Stith and Cabranes. In 1986, about 87 percent of all convictions in federal courts resulted from guilty pleas; the proportion increased to 90 percent in 1994 and 92 percent in 1995.

Former U.S. Attorney DiGenova says the guidelines have combined with other get-tough legislation approved by Congress in recent years to shift power to prosecutors.

“There is no question that the existence of federal sentencing guidelines, money-laundering laws and forfeiture laws have created horrible, horrible disadvantages for defendants in terms of negotiations,” DiGenova says. “There is just no question that prosecutors have a much greater degree [of control] over the process than they had before.”

For his part, Pozner says the guidelines have “massively” reduced defendants’ ability to plea bargain. “The guidelines have been a disaster,” he says. “The prosecutor lost discretion. The judge lost discretion. They’ve killed our ability to create justice in the criminal-justice system.”

Law professor Raeder also criticizes the federal guidelines and contrasts them to similar systems adopted in the states. “In state systems, there’s much more give and take as to how the guidelines operate,” Raeder says. “Federal guidelines are much more rigid.”

Criticisms of the guidelines have come from all quarters. Despite the pro-prosecution tilt in the guidelines, Miller says that he heard uniformly negative comments about them when he spoke to a meeting of former U.S. attorneys recently. Supreme Court Justice Stephen G. Breyer, one of the architects of the guidelines first as a senior Senate Judiciary Committee staffer in the late 1970s and then as a member of the Sentencing Commission, has complained that they are too complex and leave too little discretion for judges.

Problems with the guidelines have been exacerbated by a political stalemate between the White House and the Republican-controlled Senate over appointments to the Sentencing Commission. The commission has been without any members since October when — after working for a year with three vacancies — the chairman resigned and the terms of the three remaining commissioners expired. The White House has rejected candidates submitted by Senate Republicans, who in turn have balked at names submitted by the administration. In his annual report on the federal judiciary, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist said the “egregious” failure to fill the vacancies was “paralyzing a critical component of the federal criminal justice system.”

Still, no one expects significant changes in the guidelines from Congress. “All of the handwringing from academics and the criminal-justice community has not been able to persuade the politicians,” Raeder says. “That’s because politicians are still viewing this as being tough on crime.”

“There is tremendous support for the guidelines in Congress,” DiGenova concludes. “Regardless of their flaws, I don’t see any prospect for them being repealed or rolled back substantially.”

No Change in Sight

Like the proverbial elephant examined by blind men, plea bargaining appears quite different to the different players in the criminal-justice system. Most prosecutors and defense lawyers approve of the practice — though for quite different reasons. A few prosecutors, however, criticize plea bargaining as soft on crime and purport to abolish or at least restrict the practice. Some crime victims also criticize the practice even while their lobbying groups note some of the benefits for victims in avoiding trials and gaining assured convictions.

Defense lawyers, largely powerless to change the practice, complain about their unequal bargaining position and call for some changes to level the playing field, such as providing enhanced pretrial discovery or barring plea bargains in exchange for testimony. Many civil liberties advocates share some of those positions. A few go further and call simply for abolishing the practice — a position dismissed as patently unrealistic by prosecutors, defense attorneys and judges alike.

For their part, judges approve of the practice as a valuable tool for managing criminal caseloads while simultaneously professing to reserve to themselves the final power to accept or reject a plea and to determine the defendant’s sentence. In fact, the judges’ power is largely theoretical: Few judges reject pleas or alter sentences once the prosecutor and defense lawyer have reached their bargain.

One point, however, commands virtually universal agreement. The likelihood of significantly changing the process is somewhere between slim and nonexistent.

Prosecutors themselves acknowledge the implausibility of the recurrent claims by a few of their colleagues to have eliminated the practice. “Even among those prosecutors who say they’ve abolished plea bargaining, there’s a known ‘going rate’” for sentences, says Jim Polley, a spokesman for the National District Attorneys’ Association. “There are shortcuts that the system allows.” For their part, victims’ groups are primarily interested in ensuring that crime victims have an opportunity to be heard at some point prior to sentencing, and many states have adopted such changes.

As for defense lawyers, those who practice in federal courts argue strongly for revising — or scrapping — the federal Sentencing Guidelines, but acknowledge that is not going to happen. To be better able to plea-bargain for their clients, defense lawyers also want to receive more information about the prosecution’s case before trial, in both federal and state courts, but changes in that area are also unlikely. On the Singleton leniency-for-testimony issue, some say Congress should change the law to guard against perjury by requiring independent corroboration of any evidence given by a plea-bargaining accomplice. But any prospects for Congress to take up the question died when the 10th Circuit wiped out the ruling and upheld existing practice.

Thus, for the moment, there appears little likelihood of any significant changes in plea bargaining. “There are virtually no rules, and it might be impossible to write firm rules,” says former prosecutor Fisher. “Generally, to keep the bargaining process fair, we depend on having judges and prosecutors who want fair outcomes and on good and fair defense lawyers.”

—–

Should prosecutors be allowed to promise defendants leniency in return for testifying against an accused accomplice?

Pro

Trading leniency for testimony is an indispensable and ingrained part of our criminal justice system. Why? Simply because most criminals go to great lengths to avoid leaving evidence upon which law enforcement agents might build a case against them. While law enforcement agencies are becoming increasingly sophisticated in using electronic surveillance and scientific analysis to investigate cases, the reality remains that many, if not most, crimes simply cannot be solved by such methods. Thus, the criminal-justice system continues to depend upon the time-honored practice of using insiders — that is, criminals who themselves have participated in the very crimes under investigation — to bear witness against their erstwhile confederates. Unfortunately, such individuals typically are unwilling to assist prosecutors out of a sense of civic duty and are unlikely to respond to a subpoena. Rather, to secure their assistance prosecutors must offer an inducement: leniency. The exchange of leniency for testimony has consequently become a mainstay of the criminal-justice system. Some critics are quick to object that accomplice witnesses are inherently unreliable. They complain that prosecutors are relying on criminals who have an interest in shifting the blame to others, especially those against whom they are testifying, and are prone to shade their version of events to curry favor with their prosecutor-sponsors. These critics have a point. But they are unable to offer a workable alternative. Moreover, they fail to acknowledge the existence of meaningful safeguards against abuses. Prosecutors are required to disclose testimony-for-leniency deals so that an informant’s bias and incentive to lie may be fully explored before the jury. Additionally, several jurisdictions require accomplice testimony to be corroborated before it can be submitted to a jury. It is also common practice among prosecutors — although not common enough — to go back on a deal if an accomplice witness is found to have lied and prosecute the witness to the full extent of the law. Put another way, those who complain about the use and abuse of accomplice testimony are, in fact, expressing a lack of confidence in the jury system. As long as we believe that jurors are intelligent and discriminating and can discern the difference between reliable and unreliable evidence, there is no need to limit the use of accomplice testimony. |

Con

The unavoidable truth is that purchased testimony is inherently unreliable. Yet purchased testimony is now the favorite tactic of prosecutors with weak cases. If indeed the conspiracy charge is the darling of the federal prosecutor’s nursery, then the “cooperating witness” is the midwife. Changes in federal sentencing law in 1984 and 1986 gave prosecutors — not judges or juries — the sole power to say who does time and who does not. Now it is the prosecutor who also determines the length of a defendant’s sentence, by his charging decisions, and later often on a motion to reduce the sentence for “substantial assistance in the investigation or prosecution of another. “The decision by the 10th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in the Singleton case emphasizes that the condition of the promise is truthful testimony. But as the Supreme Court noted in Washington v. Texas (1976), ”Common sense would suggest that [a cooperating witness] often has a greater interest in lying in favor of the prosecution rather than against it, especially if he is still awaiting his own trial or sentencing.“ Desperate to get a reduced sentence, jailhouse informants listen for new cases and race to ”get on the bus“ — testify against persons they perhaps do not know but learned of through the grapevine. Faced with a lengthy prison term, desperate defendants are eager to please the prosecutor. Indicted individuals suddenly “recall” incriminating conversations with the prosecutions’s targets. Whatever the prosecution is missing is suddenly filled in — and if they don’t know enough about a case to cut a deal, they will make things up. Prisoners will do what they need to do to reduce their sentence. The Singleton court posits that a prosecutor himself could be prosecuted for suborning perjury. True in theory this is not the case in practice. The Chicago Tribune recently examined 381 murder cases around the country since 1963 that were reversed because prosecutors knowingly used false testimony or concealed evidence of innocence. Yet not a single prosecutor in those cases was ever brought to trial for criminal misconduct. Instead, the Tribune notes, the cheating prosecutors were usually rewarded with promotions. For snitches, the incentive to provide testimony is whatever gets them their deal, truthful or not. Prosecutors reward informants for convictions, not truth. This is the way the system works in real life. It’s time to change the system. It’s time to stop the government from bribing witnesses. |

| Chronology | |

| Before 1900 | Plea bargaining becomes widespread in the United States despite recurring judicial opinions disapproving of the practice. |

| 1901-1960 | Plea bargaining advances to become dominant method for disposing of criminal cases in federal and state courts. |

| 1934 | American Law Institute says courts could not operate without plea bargaining. |

| 1960s | Plea bargaining gains greater attention from courts, lawyers. |

| 1967 | President Lyndon B. Johnson’s National Crime Commission urges that plea bargaining be recognized, brought into the open and regulated by judges. |

| 1968 | American Bar Association adopts standards governing plea bargaining. |

| 1969 | Rule 11(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure requires judges to inform defendants of rights before accepting guilty plea; Supreme Court says Constitution imposes similar requirement. |

| 1970s | Plea bargaining is embraced by U.S. Supreme Court but comes under attack from liberals and conservatives, for different reasons. |

| 1970 | Supreme Court upholds guilty plea by murder defendant despite his denial of responsibility for killing (North Carolina v. Alford), giving rise to the “Alford” plea. |

| 1971 | Chief Justice Warren Burger calls plea bargaining an “essential component” of justice system; Supreme Court ruling in Santobello v. New York requires prosecutors to fulfill any promise made in plea negotiations. |

| 1973 | President Richard M. Nixon’s National Crime Commission recommends abolition of plea bargaining by 1978; New York legislature passes tough anti-drug law, barring plea bargaining for serious offenses. |

| 1975 | Alaska attorney general adopts statewide ban on plea bargaining; the ban remains in effect until 1985 and is then eased. |

| 1978 | Plea bargaining remains largely unchanged in most jurisdictions despite calls to prohibit or restrict the practice. |

| 1980s | Congress and the states move toward “determinate sentencing” schemes, with guidelines for judges to use in setting prison terms. |

| 1984 | Congress establishes federal Sentencing Commission to promulgate sentencing guidelines for criminal cases; guidelines take effect in 1987. |

| 1989 | U.S. Attorney General Richard Thornburgh seeks to limit plea bargaining by federal prosecutors, but effect of policy is doubted. |

| 1990s | Congress and states toughen sentencing laws with mandatory minimums and repeat-offender provisions; changes intensify criticism of guidelines. |

| 1993 | U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno says plea bargaining is “not incompatible” with sentencing guidelines. |

| 1994 | California voters approve “three-strikes” law, providing prison terms of 25 years to life for some three-time offenders. |

| July 1, 1998 | Federal appeals court panel in Denver undercuts plea bargaining by ruling in United States v. Singleton that prosecutors cannot offer immunity to defendants in exchange for testifying against accomplices. |

| Jan. 8, 1999 | Singleton decision reversed by full appeals court; defense attorney says he will ask Supreme Court to review case. |

Most criminal cases in the United States are resolved by plea bargaining, whether the defendants are celebrities or unknown criminals, mob figures or disturbed teenagers.

Austin Offen Austin Offen |

Austin Offen — The New York City man pleaded guilty on Jan. 6, 1999, immediately after jury selection in his second trial, to the reduced charge of first-degree assault for the racially charged beating of a black man during a brawl in a nightclub parking lot; due to be sentenced to 10 years in prison, he could have gotten a 39-year term.

Michael Carneal Michael Carneal |

Michael Carneal — The Paducah, Ky., teenager pleaded guilty but mentally ill on Oct. 5, 1998, to three counts of murder and other charges stemming from the 1997 shooting at his school that left three students dead and five others wounded; sentenced on Dec. 16 to life imprisonment with no possibility of parole for 25 years, the maximum term permitted under Kentucky law for a juvenile.

Theodore J. Kaczynski Theodore J. Kaczynski |

Theodore J. Kaczynski — The “Unabomber” pleaded guilty on Jan. 22, 1998, midway through trial, to 13 counts that centered on charges of transporting explosive devices with the intent to kill or maim; sentenced to four life terms; government accepted guilty plea with reprieve from death penalty as the only condition.

John J. D’Amico, Louis Ricco and Mario Antonicelli — Three reputed members of the Gambino crime family pleaded guilty on Jan. 11, 1999, to reduced racketeering charges in a plea bargain that will mean prison terms but no need to testify against the syndicate’s acting boss, John J. Gotti Jr. D’Amico and Ricco were identified by prosecutors as Gambino capos or heads of crews; D’Amico pleaded guilty to a single count of illegal gambling and faces about two years in prison; Ricco pleaded guilty to one count of loan sharking and faces a minimum term of three years and 10 months; Antonicelli, a Gambino “soldier,” pleaded guilty to one count of loan sharking and will receive at least three years and five months; Gotti, 34, son of long-time crime boss John J. Gotti, now serving life without parole, is due to go on trial later this year on extortion and other charges.

Napoleon Douglas — The Mississippi parolee pleaded guilty in federal court in Wichita, Kan., on Nov. 19, 1996, to one count of conspiracy to distribute cocaine and five counts of money laundering and agreed to testify against co-defendant Sonya Singleton. His testimony helped convict Singleton on cocaine conspiracy and money-laundering charges; she was sentenced in fall 1997 to four years in prison. Douglas was sentenced to 60 months, to run concurrently with another sentence.

Marv Albert Marv Albert |

Marv Albert — The nationally known sportscaster pleaded guilty on Sept. 25, 1997, midway through trial, to misdemeanor assault and battery for biting a 42-year-old Vienna, Va., woman during a sexual liaison; prosecutors dropped forcible sodomy charge, punishable by up to life imprisonment; placed on unsupervised probation, over prosecutors’ objection; guilty plea vacated one year later and case dismissed.

Mark Fuhrman Mark Fuhrman |

Mark Fuhrman — The former Los Angeles police detective pleaded no contest on Oct. 2, 1996, to a felony perjury charge for falsely denying during the O.J. Simpson trial that he had used a racial slur within the previous decade; sentenced to three-years’ probation and fined $200; could have faced up to four years in prison.

Michael Fortier Michael Fortier |

Michael Fortier — The Army buddy of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh pleaded guilty on Aug. 10, 1995, to four counts, including transportation of stolen firearms, conspiracy to transport stolen firearms and misprision of a felony (knowing about a crime but failing to report it); agreed to testify against McVeigh and co-defendant Terry Nichols; faced up to 23 years in prison; sentenced on May 27, 1998, after completion of trials, to 12 years in prison; government also agreed not to prosecute Fortier’s wife, Lois.

For critics of plea bargaining, the headline could not have brought better news: “Bronx District Attorney Moves to Ban Plea Bargaining in Felony Cases.” On closer reading, however, the policy pronouncement by Bronx prosecutor Robert Johnson in November 1992 was less sweeping. Johnson had instructed his staff not to plea bargain with defendants after a grand jury indictment, but they were still free to negotiate before grand jury action.

Johnson’s policy remains in effect today and has been copied by Johnson’s counterpart in another New York City borough, Queens District Attorney Richard Brown. Both prosecutors depicted the moves as aimed at moving cases through the judicial system faster and ensuring prison time for more defendants. Critics, however, say the major effects have been to create court backlogs, keep defendants in jail longer and pressure defense lawyers to plea bargain with less time to investigate a case and prepare a defense.

“They put immense pressure on you to put pressure on your client to get rid of the case when you basically know nothing about the case except what your client told you,” says Stephen S. Singer, a prominent criminal defense lawyer in Queens.

Mary DeBourbon, spokeswoman for the Queens County District Attorney’s office, concedes the policy puts a lot of pressure on defendants. But she says defendants also get a benefit. “It gives the defendant an opportunity to get a lesser sentence,” she says.

As for the prosecutors themselves, the policies save valuable time by diverting cases from grand jury presentations. “Grand jury time and space are at a premium in this courthouse,” DeBourbon says. Police and crime victims are also spared the time they would have to take in appearing before a grand jury, she notes.

Some critics have warned that the policies might backfire for prosecutors by forcing them to drop or lose cases rather than plea bargain after indictment. Both DeBourbon and Steven Reed, a spokesman for the Bronx D.A.’s office, say those fears have not materialized. “We haven’t seen a decrease in the number of felony convictions or the percentage of prison sentences,” DeBourbon says.

Both of the spokespersons also minimize criticisms that the policies have contributed to court backlogs. “There’s always been a backlog,” Reed says. “It did not create an acceleration in the backlog. That has not been an issue at the forefront.”

In fact, court statistics show that the policies have contributed to backlogs. In the Bronx, the percentage of cases pending for more than six months increased from 51 percent in 1992 — before the policy went into effect — to 60 percent a year later, according to Chester Mirsky, a professor at New York University Law School and a leading critic of the policies.

At the height of the policy, Mirsky says, “it was routinely the case that people were being detained 15 months awaiting trial in Superior Court.” The result, he says, is longer jail time for defendants and added jail costs for the city. In addition, delays can create problems for prosecutors as witnesses move away or their memories blur.

In the Bronx, Justice Burton Roberts, the court’s administrative judge, kept up a steady criticism of the prosecutor’s policy until his retirement at the end of last year. Judges’ criticism may have played a part in easing the policy somewhat over the years. Today, Justice John Collins, the current supervising judge for criminal cases, even said in an interview that Johnson had dropped the policy. Informed of the statement, however, spokesman Reed insisted the policy was unchanged.

In Queens, Steven Fisher, the administrative judge, says Brown’s policy has had no significant effect on backlog. But he acknowledges some defendants are being held in jail for longer periods. “It may be that more defendants are incarcerated for a longer time before indictment,” the judge says. “But that’s because of their own action waiving speedy indictment to allow them to engage in preindictment plea bargaining.”

Spokespersons for the two D.A.s both say the policies have paid off in better prosecutions. “Before the policy, there was a presumption on the part of defendants and their lawyers that if they waited long enough and haggled long enough, the charge would go down,” Reed says.

“We’re taking the position that cases we take to the grand jury are cases we can damn well try, and we’re ready to go,” DeBourbon says. “It’s given us back a measure of control over our workload.”

For his part, Mirsky calls the policies a “ruse.” “It’s by no means a plea-bargaining ban, it’s a ban on plea bargaining in Superior Court,” he explains. “The public is being misled, and the quality of justice is being diminished as people are being forced to take plea bargains in short periods of time or having to stay long periods of time in Riker’s Island,” the city’s main pretrial detention facility.

But Singer says controversies over the policies have largely died down. “This system is oppressive and unreasonable,” he says. “But it’s good from the prosecution standpoint, and taxpayers save money over the long run.”

[1] The New York Times, Nov. 25, 1992, p. B3.

[2] The New York Times, May 16, 1996, p. B3

[3] See Chester L. Mirsky and Gabriel Kahn, “No Bargain,” The American Prospect, May/June 1991, pp. 56-57.

Ralph Buchanan faced up to life imprisonment when he was arrested in Florida on federal drug charges. To try to soften the penalty, Buchanan agreed to plead guilty and to cooperate with prosecutors in solving an unrelated crime.

As part of the plea bargain, Buchanan agreed to give up the right to appeal whatever sentence the judge imposed. Federal prosecutors around the country often require such appellate waivers from defendants before agreeing to a plea bargain.

Unfortunately for Buchanan, the government could not solve the crime despite his help. So when the time for sentencing came, the prosecutor argued — and the judge agreed — that Buchanan was not entitled to a “downward departure” under the federal sentencing guidelines.

Instead of the 10-year prison term Buchanan had expected, he got a life sentence. And when he attacked the fairness of that decision on appeal, the federal appeals court in 1997 refused to hear him, saying that he had waived any right to appeal as part of a valid plea bargain.

Buchanan’s case provides one dramatic illustration of an increasingly common practice that federal prosecutors love and defense lawyers hate.

“More prosecutors than ever are requiring some sort of appellate waiver on a plea agreement,” says Bruce Hanley, a criminal defense lawyer in Minneapolis. “They ram it down your throat.”

So far, federal appeals courts have upheld the waivers. But some appellate judges have expressed reservations, and at least one federal district court judge in Washington, D.C., says he will not enforce them.

“The condition sought to be imposed by the government is inherently unfair,” Judge Paul Friedman wrote in a December 1997 ruling. “This Court therefore will accept no plea agreements containing wavier provisions of this kind.”

The Justice Department, however, strongly defends the practice. “[T]he use of these waivers in appropriate cases can be helpful in reducing the burden of appellate and collateral litigation involving sentencing issues,” John Keeney, acting assistant attorney general for the criminal division, wrote in a memorandum for all U.S. attorneys in October 1995.

Any plea bargain entails a defendant’s relinquishing fundamental rights — like the right to cross-examination of the government’s witnesses and the right to a jury trial. Appellate waivers are different, according to the critics, because the defendant is being asked — under pressure — to give up the right to contest a sentence yet to be determined. In addition, many prosecutors include provisions for the defendant to waive any right to so-called post-conviction relief — for example, overturning a conviction on grounds of ineffective assistance of counsel.

Prosecutors have turned to appellate waivers because of the increasing number of sentencing issues that defendants are raising in appeals under the federal sentencing guidelines. The guidelines, which went into effect in 1987, raise a host of legal issues because of the complex calculus of factors used in determining a defendant’s sentence and the judge’s discretion — within limits — in applying them.

“In a plea agreement we cannot pin the judge down,” Hanley explains. “There are so many exigencies that the defense lawyer and the prosecutor have no control over. A defendant needs to have the opportunity to challenge some of that stuff on appeal.”

Hanley tried to get the American Bar Association’s criminal justice section to adopt a resolution in late 1996 discouraging the use of appellate waivers and in any event guaranteeing a defendant’s right to appeal any sentence higher than provided for by the sentencing guidelines. But the ABA unit took no action on the measure.

The U.S. Judicial Conference did send federal judges a policy memorandum earlier in 1996 recommending that defendants be specifically advised of their appellate rights before any waiver is accepted in court. But the memorandum gave no specifics about what judges should tell defendants.

For his part, Hanley says he refuses to agree to the kind of broad waiver that many federal prosecutors ask for. He says he never gives up a defendant’s right to challenge a sentence for going beyond the guidelines or to raise constitutional claims in post-conviction proceedings.

In one ruling in 1997, the federal appeals court in New York indicated doubts about the validity of the broadest kind of appellate waivers.

“It seems to me that the law is clear,” says Joseph DiGenova, a former U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia. “If it’s a knowing waiver, that’s the ballgame.”

[1] See Lynn Fant and Ronit Walker, “Reflections on Hobson’s Choice: Appellate Waivers and Sentencing Guidelines,” Federal Sentencing Reporter, Vol. 11, No. 1 (July/August 1998), p. 60.

[2] The case — United States v. Raynor, decided on Dec. 29, 1997 — is reprinted in Federal Sentencing Reporter, Vol. 10, No. 4, January/February 1998, pp. 234-238.

[3] Ibid., pp. 209-211.

[4] For a summary, see ibid., pp. 212-214.

[5] United States v. Rosa, 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Aug. 19, 1997, reprinted in Ibid., pp. 228-33.

Books

Forer, Lois G. , A Rage to Punish: The Unintended Consequences of Mandatory Sentencing, W. W. Norton, 1994. Forer, a judge on Pennsylvania’s Court of Common Pleas in Philadelphia, mounts a sharp attack on mandatory-sentencing laws and sentencing guidelines. The book includes source notes. Forer’s other books include Crime and Victims: A Trial Judge Reflects on Crime and Punishment (Norton, 1980); in both books she defends plea bargaining and judicial discretion in sentencing.

Friedman, Lawrence M. , Crime and Punishment in American History, Basic Books, 1993. Friedman, a professor at Stanford Law School and one of the country’s leading legal historians, traces the history of the U.S. criminal-justice system from Colonial times to the present. The book includes detailed source notes and an eight-page bibliographical essay.

Herman, G. Nicholas , Plea Bargaining, Lexis Law Publishing, 1997. The book, intended as a practice guide for lawyers and law students, provides detailed, step-by-step explanations of the plea-bargaining process along with up-to-date citations to relevant cases, legislation, and Sentencing Commission materials. Herman is a defense lawyer in Chapel Hill, N.C., and an adjunct professor at the University of North Carolina School of Law and North Carolina Central University School of Law.